Sacroiliac Strain

Sacroiliac Strain

Jean Luc Cornille

Usual abbreviations and key words

(SIJ), Sacroiliac Joint. (SID), Sacroiliac Dysfunction. (VSIL), Ventral Sacroiliac Ligament. (DSIL), dorsal sacroiliac ligament. (Physeal), Relating to the area of bone that separates the metaphysis and the epiphysis, in which the cartilage grows. (SCDL), sacrocaudalis dorsalis lateralis muscle

When, in 1969 James Rooney introduced the biomechanic analysis of lameness, standardbred racehorses were particularly prone to sacroiliac dysfunction. The pathologist theorized that “the waggle-tail gait of the harness horse might well predispose to minor subluxation of one or the other sacroiliac joints, tendinous strain, etc.” (1) Rooney also observed partial luxation of one or both sacroiliac joints in jumpers. Today, jumper and dressage horses are the most affected. “In a group of 74 horses with pain in the sacroiliac joint, dressage horses and show jumpers were found to be more at risk for sacroiliac dysfunction than horses from other disciplines including racing, eventing and general purpose.” (2)

Several hypotheses may explain the actual increase of sacroiliac dysfunctions, (SID), in the dressage field. One rational thought is that new training techniques are creating abnormal stresses on the sacroiliac joints. Another possibility is that traditional training approaches are no longer capable of efficiently preparing the horse’s physique for the athletic demand of modern performances. A third perspective is that when those, with insufficient knowledge of equine biomechanics, attempt to teach specific movements, the subsequent physical and mental development creates a horse that is physically unprepared for the athletic demands of the performance, which then makes the body more prone to injuries.

“The role of the SIJ is to transfer the forces from the horse’s hind limbs to the thoracolumbar vertebral column. This transfer of forces may be achieved via connection of the ligaments particularly the DSIL and the sacrotuberous ligamen, and the related fasciae. These ligaments are anchored through the thoracolumbar and gluteal fasciae and the hamstring sacrotuberous ligament complex.” (4). Below the sacrum is the very strong Ventral Sacroiliac Ligament, (VSIL).

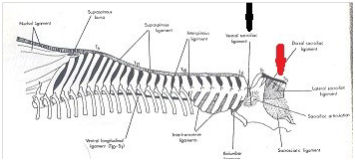

View of the main thoracolumbar spine’s ligaments. The position of the ventral sacroiliac ligament is indicated by transparence through the pelvis under the sacroiliac joint. The red arrow shows the short DSIL

Above the sacrum and connecting to the tuber sacral is the dorsal sacroiliac ligament, (DSIL). The DSIL is composed of two elements. One is a cord like portion that runs from the dorsal aspect of each tuber sacrale to the apices of the sacral spinous process. This element is referred to as the short DSIL.

Hastened and superficial education places horses in the Grand Prix ring before they have reached physical maturity. In 2009, Kevin Haussler recorded deformations of the equine pelvis under load. “The bones of the pelvis are not a rigid structure and bony pelvic deformation is a normal occurrence in any sacroiliac joint movement.” (3) The degree of deformation varies with age. Equine pelvis physeal closure occurs at 5 years of age (plus 2 to 8 months). Iliac crest formation and fusion to the underlying bone occurs at 7 years. Therefore, a dressage horse entering the Grand Prix Dressage ring at age 7 is not structurally ready for the intensity of the athletic demand.

SID is primarily a training disease. In a few instances dysfunction can occur from dramatic trauma but most often, dysfunction is the outcome of repetitive abnormal stresses. Training misconceptions, such as compelling the horse to speed around the ring, are abnormally stressing the sacroiliac joint, (SIJ). In two cases that we have rehabilitated the problem was that the training techniques applied were ill adapted to the horses’ particular morphology. As a generality any training program that submits every horse to the same order of priorities places each individual horse at risk of SID. The anatomy of the SIJ clearly exposes its deep relation with forward motion, balance control and performance. A clear distinction needs to be made between learning to show and learning to ride. Learning to show is about submitting the horse to judging standards without sound understanding and concern for the athletic demand imposed on the horse’s physique by the performance. Learning to ride focuses on preparing efficiently the athlete’s physique in preparation for the demands of the performance. The former is the main cause of SID. The latter is the best therapy for prevention or treatment of sacroiliac dysfunction.

Based on manipulations applied to humans a battery of manipulations have been proposed for the horses’ rehabilitation. However, while a human is likely to participate in the manipulation knowing that some pain during the therapy session might lead to better reeducation in the future, the horse, which lives in the moment, is more likely to protect himself from any stimulation of pain, thereby resisting the movement that the therapy is suggesting. The movements suggested, as therapeutic manipulations, can be recreated while riding the horse or working the horse in hand. Whether mounted or in hand, such an approach demands equitation based on actual knowledge of equine physiology as well as correct symbiotic positioning while working from the ground. Both of which in turn creates more effective therapeutic movements. Basically, an educated equestrian may be the horse’s best therapist.

The complete PDF file which is availible for purchase here

On a DVD or as a Download.