Quolibet Z Part 4

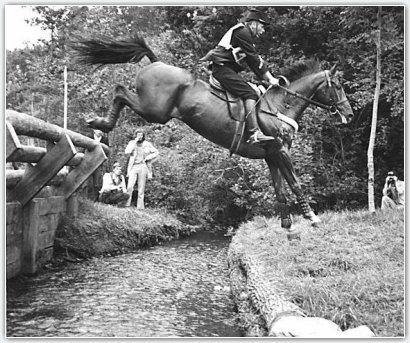

Jean Luc Cornille and Quolibet Z at Pompadour

Selection trail for the world championship

Quolibet Z

Part IV

If I had had my say, I would have retired Quolibet from international competitions after the World Championship. In three years, he went from death row to the World Event. He completed one of the most challenging cross-country courses ever built primarily due to his rational thinking and generous heart. His successes were not attributable to extraordinary athletic abilities. If I had had my say, I would have given Quolibet to a talented young rider. He loved his work; he liked the long Pignot jogs, and he truly enjoyed the weekly two-hour walks on long reins in the Fontainebleau forest. He would never have been happy in full retirement. The difficulty level of the young riders' competition would have been recreational for Quolibet. He would have taught to one or more talented young riders that the training scales are not the equestrian education's purpose by any means. They are only the canvas upon which skilled riders and gifted horses express their talents.

Great horses and promising riders are destroyed by the preposterous idea that every athlete should be submitted to the same training regime. Often, the casual conversations that we had between riders and guest riders of the Fontainebleau's Olympic Center delved into the training scales' subject. The principles varied from one school to the other, but the discussion was really about the limitations created by any system. As early as 1949, General Decarpentry addressed the issue. "The officer who decides to prepare a horse for international dressage tests is going beyond the limits of his equestrian education." (General Decarpentry, Academic Equitation, 1949) No one questioned the fact that the demands of equine athletic performances were beyond the limits of conventional education. The conversations were about how early in their careers skilled riders should explore beyond the system. Each rider coming to the center had his or her own Quolibet story. While the large majority of the horses were well-bred athletes coming into the competitive world with an expensive price tag, some horses were damaged by a training system that crippled their athletic abilities. Not one of these horses ever revealed their hidden potential when confined to the very same system which shattered their talents in the first place. Any horse's resurrection was the result of a rider's ability to think outside the box.

I remember an extraordinary jumper. His name, if my memory is accurate, was Mon Rose. The horse had tremendous power and a terrible style. He was so inverted over the jumps that the rider told us that the most uncomfortable detail with this horse was that he looked him straight in the eyes as he was flying over the jumps. The horse's career was quite disastrous because the trainer tried to fit the horse to the stereotypes that he was familiar with. Michel Roche came into the picture realizing that this extraordinary horse needed to be ridden the way he wanted to be ridden. Michel adapted to the horse's peculiar style. Then, they both met another genius. Jean Dorgeix was the coach of the French jumping team. He realized that the combination of Mon Rose and Michel Roche was as exceptional as it was unconventional. Dorgeix selected Michel Roche and Mon Rose for the Olympic squad. They won the team Gold Medal at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

The French school promotes the thought that the rider's hands should be categorized into five specific actions: the rein effects. Quolibet truly disliked the rein effects. I thought at first that painful memories guided his reluctance. Perhaps inexperienced students had pulled on his mouth when he was a school horse. I tried to apply discreet rein effects, but his aversion did not diminish. Since I wore the uniform of a school whose mission is to protect and perpetuate the French equestrian tradition, I could not say that my horse did not want anything to do with the rein effects. Basically, I rode one way and taught another.

Sometimes, the extreme discretion of my rein effects was questioned by the judges. They wanted to be sure that I was in accordance with the system. I explained that I had to be very quiet about moving my hands because Quolibet was hyper-sensitive to any hand movement and traction on the reins. Knowing the power of classical quotes, I referred to the author of the masterpiece Academic Equitation, "Hand movements diminish as dressage progresses to the point of giving an illusion of immobility." (General Decarpentry, Academic Equitation, 1949. J. A. Allen & CO LTD. 1971 p. 44). This was a powerful argument. No one could dispute Decarpentry's authority, even if Decarpentry never referred to the rein effects for the straightforward reason that they were not invented when Decarpentry wrote the book!

Since I am talking about the five rein effects, maybe I should quickly review the theory. The more simple one is known as la reine d'ouverture (the opening rein), which is an action of the rider's inside hand moving toward the inside of the circle and pulling the horse's head and neck toward the inside. The horse is then supposed to follow his head and neck's direction and turn on a circle or only into the indicated direction. The second rein effect is known as la reine d'appui (the indirect rein). Exerting a light pressure of the rein on the neck is supposed to push the horse's shoulders in the opposite direction. The third effect is referred to as la reine direct d'opposition (direct reins of opposition). The thought is to oppose a résistance by placing the inside rein parallel to the horse's body and acting in the direction of the inside hip. The theoretical effect is that such rein action tends to displace the horse's haunches in the opposite direction.

The fourth effect is labeled as reine contraire d'opposition en avant du garrot (contrary or indirect rein of opposition ahead of the whither). Fortunately, this rein effect is easier to execute than to read. The rider's hand acts ahead of the horse's whither in the direction of the outside hip. The theoretical effect is that this rein effect pushes the horse's shoulders to the outside and the haunches to the inside. The fifth effect is named reine contraire d'opposition en arriere du garrot (indirect rein of opposition behind the whither). This rein effect is also referred to as intermediary rein, la reine intermediaire. The rider's hand acts above or behind the horse's whither in the direction of the middle of the croup. The theoretical effect is that the intermediary rein pushes the horse's whole body toward the outside.

Like every so-called rider aid, the rein effects are based on an element of truth. An uneducated horse might respond to one or the other rein effects by moving his body approximately as described in the rule book. However, believing that the horse's reaction will be systematic is a stretch. A horse is not genetically wired to know the rein effects by birth. Like Pavlov's dog, a horse may be conditioned to respond to any rein action, but he will protect existing muscle imbalance, weaknesses, or morphological flaws.

An event that occurred at Saumur as I was a teenager exposed the narrowness of equitation based on formulas. The Cadre Noir de Saumur was opening to civilians by offering two-week sessions of intensive training. I was a teenager and thrilled to have been selected. Each afternoon, the training sessions ended in a classroom with two hours of equestrian theory. The instructor was a member of the Cadre Noir. He was an extraordinary figure with his cigarette holder and monocle. I perceived him to be very intelligent and perhaps a visionary. The subject of the theory was Monsieur de la Gueriniere's shoulder-in. La Gueriniere wrote, "Instead of keeping a horse completely straight in the shoulders and the haunches on the straight line along the wall, it is necessary to turn his head and shoulders slightly inward, toward the center of the school, as if one wanted to turn him, and when he has assumed this oblique and circular posture, one must make him move forward along the wall while aiding him with the inside rein and leg, (he absolutely cannot go forward in this posture without stepping-over or "chevaler" the front inside leg over the outside and, similarly, the inside hind leg over the outside." (Francois Robichon de la Gueriniere, Ecole de Cavalerie) We had been told to commence the shoulder-in by utilizing the opening rein and then pushing the shoulders in the direction of the motion using the indirect rein. Our instructor suggested instead using the opening rein all the way through the shoulder-in. We were conditioned to mathematical formulas, Opening Rein + Indirect Rein = Shoulder-In, and we were incapable of thinking beyond our dogmas. Our education was narrow-minded to the extent that the study of rein effects was the training's purpose. In our elemental thinking, we believed that the horse would move on a circle if we were not using the indirect rein.

Our instructor was surprised by our group's reaction. The two theologians of the group then defiantly questioned his views. I could see perplexity in his body language. He went inside his mind to the memory of his last riding session, placing his hands and body as he did when practicing Shoulder in. Then he looked at us. Annoyance had now supplanted perplexity, and he calmly ended the session, saying, this is the way I will teach Shoulder- in to you if you want to learn. I was very uncomfortable with the situation, as I was the youngest member of the group and not secure enough to take a position. The theologians drew up a formal complaint, and another instructor was assigned to our group.

The same night, I thought of the man's body language as he reviewed in his mind the way he asked for shoulder-in. He was inviting us into a more subtle world, but we were so compartmentalized in our little knowledge that we could not see and think beyond the five rein effects' academic application.

Two days later, I approached Capitan de Croutte and asked if he could elaborate on his thought about the shoulder-in. He smiled, telling me if you are ready to think, yes, I will gladly give you the explanation. In a short conversation, he brought everything back into perspective. The rein effects are not the purpose of your education. They are a teaching technique aimed at organizing your hands' actions. Your hands are only small components of your entire body. Any conversation with your horse is not about hand signals but rather body language. The ingenious idea of the shoulder-in is the attitude oblique and circular, which favors the lowering of the inside haunch. Monsieur de la Gueriniere said, "When the horse has assumed this oblique and circular posture, you must make him move forward along the wall while aiding him with the inside rein and leg." There are many ways you can help the horse to move forward along the wall with your seat and legs, keeping your inside rein in its opening position. You do not have to push the horse's shoulders sideways, exerting pressure with your inside reins on the base of the neck. If you do so, you will lose either the horse's lateral bending or the placement of the horse's shoulders one foot and a half to two feet toward the inside of the ring. I thanked him, asking if I could take advantage of his knowledge in the future by asking more questions. He told me yes, of course, anytime.

Anytime occurred more than a decade later. De Croutte had pursued an advanced military career. I instead had taken advantage of the military corps to advance my riding career. I was back into civilian life, and de Croutte has been promoted to colonel. He was the head Riding Master of the superior school of military studies in Paris. We were almost neighbors. We met many times, as the Paris Military School organized jumping and dressage competitions.

Interestingly, we continued the conversation as if it had started the day before. He was interested in the practical application of classical views to the demands of modern competitions. We both agreed that the problem was not the classical views but rather the narrow-minded views that theologians promoted. One saying of the Cadre Noir of Saumur is, "Respect for tradition should not prevent the love of progress." (Colonel Danloux) Progress involves advances in scientific knowledge. However, already at that time, theologians were selecting and interpreting pertinent scientific discoveries to accredit their beliefs. Nothing has changed. In 2009, the psychologist Jonathan Haidt said, "We engage in moral thinking not to find the truth, but to find arguments that support our intuitive judgments" (Jonathan Haidt, 27 September 2009)

The subject of the shoulder-in is fascinating. Actual judging standards score the horse for its ability to sustain an angle of 30º to the rails and with the limbs traveling on three tracks. Better judges may also look at the horse's ability to maintain cadence and suspension. Neither Monsieur de la Gueriniere nor the Duke of Newcastle who inspired la Gueriniere ever talked about an angle of 30º or the number of tracks. La Gueriniere's words were, "The line of the haunches must be near the wall, and the line of the shoulders must be about one foot and a half to two feet away from the wall." That the horse's body formed an angle of 30º with the rail was an observation made a century later. Gustave Steinbrecht was a detail-oriented type of person. His book, The Horse Gymnasium, narrates in incredible detail all the gestures, actions, and reactions he observed in training advanced level horses. Steinbrecht noticed that best results were achieved in the shoulder-in when the horse's body formed approximately an angle of 30º with the rail. Steinbrecht also observed that when the horse was sustaining such an angle, the limbs traveled on three tracks.

The same narrow-minded compartmentalization, which decades earlier kept our group of young theologians within the limits of rigid formulas, Opening Rein + Indirect Rein = Shoulder-In, is today severing modern equitation from the real benefits of the beautiful gymnastic exercise known as the shoulder-in. Interestingly, Gustave Steinbrecht restored the shoulder-in's real meaning, preparing the move with horse body coordination that he named shoulder-fore. Steinbrecht advised using the inside leg and outside rein. Today, the formula, Inside leg + outside reins = Shoulder fore, Shoulder- in, Straightening the horse's body, Taking care of the flue, Winning a blue ribbon, etc., etc.

Watching Quolibet's style over the jump, Pierre Dinzeo's remark was closer to Steinbrecht and la Gueriniere's idea than any dressage formula later invented. Steinbrecht did not introduce the shoulder-fore as a dressage movement but instead as a concept: a body coordination to efficiently prepare the horse's physique for the shoulder-in. La Gueriniere did not introduce the shoulder-in as a dressage movement but instead as a gymnastic. "This lesson produces so many good results at once that I regard it as the first and the last of all those which are given to the horse."

When I first placed Quolibet under my umbrella, my only goal was to ease the last five months of his life. It was then easy to explore beyond traditional thinking. The system had failed Quolibet, both physically and mentally, and the thought that if there were a solution, it would likely be out of the box was a rational working hypothesis.

I will never thank Quolibet enough; first, that he was who he was. Also, because his dramatic situation directed my thought toward applying advancements in scientific knowledge exclusively for the good of the horse, I am grateful to him. Later, as Quolibet started to be successful in competition, I deviated, using progress in scientific knowledge to gain one more success. Fortunately, Quolibet's partnership had tempered my sense of competitiveness with a sense of decency. The fever of winning took over many times, but I had evolved and so pursued foremost the thought that the science of winning meant that a real victory involves the happiness and soundness of both the rider and the horse.

I did my share of indecencies, pushing horses beyond their limits, or entering the show ring when I should have rested the horse. The memory of Quolibet's teaching tainted these ephemeral glories so darkly that in my memory now, these victories are more embarrassing than glorious. There have also been other extraordinary horses and extraordinary men. The next horse presented in my greatest teachers' stories did not come into my life directly after Quolibet Z. Still, if it were a rational order in the evolution of life's lessons, Vanzep would have been the next partner.

Jean Luc Cornille

Copyright©2010 All rights reserved