Quolibet Z Part 3

Quolibet Z Part 3

by Jean Luc Cornille

Quolibet was an ordinary jumper who, due to his mind and heart, achieved out-of-the-ordinary performances. Quolibet was comfortable over four-foot jumps, but he was athletically challenged when the jumps were higher than five feet. Quolibet's greatness was his courage; he always tried. Sometimes he took off and improvised once he was flying over the jump. His faculty of improvisation allowed him to pull us out of some difficult situations. At Punchestown, for instance, it was a jump that was impossible to rationalize. It was a shallow ditch followed by a round-shaped bank, another shallow ditch followed by a similar bank, a third shallow ditch, a third bank, and a large oxer over a fourth shallow ditch. The problem was that the distance between the top of one bank to the other bank's top was too long to allow a jump. One solution was trotting up and down the banks and the ditches. The other was jumping the ditch then landing halfway up on the side of the bank. Then descend halfway through the middle of the other side, jump the ditch, landing uphill on the other bank, and so on. The trot solution was safe, but the horse needed to have a lot of power to propel himself over the large oxer since the forelegs would be lower than the hind legs for the take-off. Quolibet did not have the power to do it this way. I opted for the canter solution. He took off over the oxer the best he could but realizing that his hind legs would not make it, he twisted his vertebral column placing his hind legs excessively sideways.

The Irish flavor of the story is that while all the riders from other countries were scratching their heads trying to figure out how to negotiate the "question," the Irish team told us that they were jumping this type of combination all the time while fox hunting. Ironically, one after the other, the Irish riders all had trouble with this specific combination, and as a result, they were forced to change the music. They told us that the cross country course was challenging because the course designer worked in the afternoon and was always drunk after lunch.

When he was a school horse, Quolibet's style over the jumps was precarious. Upon my arrival at the school, Quolibet was introduced to me as a horse having a major attitude problem and a dangerous technique over the jumps. During the next few weeks, I started to disagree with the judgment. I did not see Quolibet as a horse trying to kill the students but rather as a horse trying to survive. He was stiffening the neck and pushing heavily on the bit to protect himself from inexperienced riders pulling on the reins. As a result, he was rushing toward the jump heavily unbalanced on the forehand. He was taking off far away from the jump, which was a wise decision. He was so much on the forehand and so rigid in his back that he could only jump long and flat. One day, I even watched him landing on the other side of the jump with the hind legs first. The rider was leaning backward, screaming for help, holding the reins as hard as he could. That same day I removed Quolibet from the lesson program. The students were thankful for the move, but it was more out of concern for the horse in my mind. Enough was enough, and this poor horse could not endure this nightmare much longer.

Months later, anticipating a problematic reeducation, I reintroduced Quolibet to the jump at the walk. The technique is handy. Without the benefit of momentum, the horse has to think about a more efficient use of his physique. The first jumps are often a little bumpy, but the horse's brain soon explores a more efficient solution. Quickly, Quolibet's mind explored the thought that suppleness may be more efficient than power. Soon, he resolved the jumping question fluidly and efficiently. As he landed at the canter, calm and composed, I continued at the canter coming back on the same jump. It was a picture-perfect performance. The take-off was in the base, the jump was supple, and the landing was effortless. I patted him, and we walked back home. This was pretty much the extent of Quolibet's reeducation. The next training session started where this one ended. As I was suspecting, Quolibet's previous behavior was only a defense mechanism. Once there was no reason for him to protect himself, his attitude changed.

Quolibet initiated the thought that a true partnership between a human and equine is about two different levels of intelligence working together; the human, who has the capacity of analysis and may set-up the horse for success, and the equine, who can best process the most efficient solution. Quolibet was not the best about placing the take-off stride accurately, but he was an acrobat once airborne. We gradually developed a tacit agreement. I was in charge of placing the take-off at the right spot, and he was assuming authority for the rest. Quolibet was perfectly willing to let me adjust take off, speed, and trajectory for the first element in a combination, for instance. As soon as he took off, Quolibet was in charge.

I was usually able to see the distance and adjust the take-off four strides before the jump. This would allow enough time to shorten the last four strides when the distance was a little short or, on the contrary, lengthen the last four strides when the distance was too long. However, like every rider, I was some time in the fog. The expression being in a fog was made popular by Marcel Rozier, who later became the coach of the French jumping team. Marcel was very well known for his superior ability to adjust the take-off stride. His eye was legendary. Once, during a jumping course at Fontainebleau, Marcel missed three times the correct adjustment and three times the horse saved the situation. He walked out of the ring, shaking his head, and commented, "I am going to write a book, 'Fifteen Years In The Fog Or My Life As A Rider.'"

Quolibet always took off where I asked him to take off. His greatness was his reflexes when I was in a fog. He also never punished me for my mistakes. Once at Saumur, the cross country course's difficult question was a large oxer placed on the edge of a sharp downhill. The landing was effectively 6 feet down, but the optical illusion was a 20-foot drop. To complicate the issue, the oxer was placed only four strides after a sharp 90º turn. Conscious of the difficulty, the course designer prepared the horses for the serious question with a similar oxer but without the drop. I skew the easy jump's adjustment realizing two strides before the take-off that the distance was too long. Quolibet took off where I placed the take-off stride and stretched himself over the jump as far as he could to cover the width. He folded his hind legs very tight against his stomach but hit with his toes the oxer's second element. He had to use his energy and skill to control his balance at the landing. I apologized as we were cantering toward the difficult question. I was now concerned about having shattered his confidence for the difficult jump. He did not hesitate a second. He accelerated the last four strides, flew flawlessly over the oxer, and landed in perfect balance. As we were speeding down the hill, I knew that I was riding a giant.

The psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote, "We engage in moral thinking not to find the truth, but to find arguments that support our intuitive judgments." The next days, a perfect example of the media and officials' intuitive judgment was in all equestrian magazines. Quolibet was the rising star, and each one of his moves was now interpreted as proof of his talent. The distance between the turn and the jump was very short. This was a problem for Quolibet's moderated power. I elected to adjust the distance while remaining in the turn, taking the risk of coming on the large oxer on a slightly oblique trajectory. This solution was a little challenging since it increased the jump's width but allowed in counterpart to come on the jump with more momentum. This was a calculated risk that was adapted to the horse's lack of muscular power. The next weeks in the equestrian magazines, I read comments about our performance. The rider is so confident in the horse's power that even on the most difficult obstacle of the cross country course, he takes the risk of coming on an angle in order to save a few seconds. Months earlier, the same commentators and officials questioned my judgment asking why I was wasting my time with a training level horse.

In just a few years, Quolibet had escaped from death row, became a teaching horse, and graduated into a three-day event horse. He was now at the three-day event and jumping Olympic Training Center at Fontainebleau. I had been offered to join the three-day event team, and I had asked to bring Quolibet with me. The training center was situated in the stabling area of the beautiful Fontainebleau castle. The castle was, back in French history, the residence of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Fontainebleau was a unique situation. The Olympic Center was very well equipped, and Grand Prix riders from all over Europe regularly came to the center preparing their horse for major events. On many occasions, several world-class riders were working in close proximity. They did not have to protect their stature in front of their customers, and they were not anxious to let everyone know how great they were. It was no question that they all were excellent riders. Interestingly, they were preparing their horses for the same competitions using very different techniques. This unique situation allowed enlightening conversations.

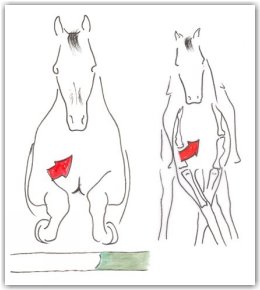

The horse's style was a frequent subject of discussion. They were not looking for a specific style, but they adapted their riding technique and training approach to their horses' style. One day, Pierro Dinzeo from Italia was riding his horse in the jumping ring where I was jumping Quolibet. I liked the Italian rider's style; he was riding on long reins, adjusting the stride without hindering the horse's movement. After my first three jumps, he quietly approached and told me, you should not warm up your horse using shoulder-in; the gymnastic does not prepare well a horse who, like your horse, is jumping, folding the knees apart from each other. Dinzeo added then, and I cannot explain to you why that. This is just an observation that I have made over years of experience. Almost fifteen years later, Jean Marie Denoix published a study explaining how shoulder-in was developing foreleg muscles serving horses' performance lifting the knees close to each other over the jump. By contrast, the gymnastic was not adequate for a horse who, like Quolibet, was lifting and separating the knees.

A horse jumping with the knees close to each other uses the pectoralus descendant muscles, which are developed during the shoulder-in adduction phase

By contrast, a horse lifting the knees apart from each other, as did Quolibet, uses the biceps brachi and omotransversarius muscles. These muscles are better stimulated during the abduction phase of the half pass.

"The best way to train a horse is to use techniques that align with the horse's view of the world." (Paul McGreevy, BVSc, MRCVS, Ph.D., MAACVSc, associate professor of veterinary science at the University of Sydney in Camden, New South Wales, Australia, 2010) Quolibet's view of the world was that as long as the take-off placement and the balance were adequately taken care of, there was no jump of the cross country course that he could not negotiate. Quolibet also had a clear understanding of his athletic limits. The few refusals that I had with Quolibet during his career were because he felt that he could not resolve the problem in the conditions where the problem was presented to him. For instance, at Punchestown, a jump reproduced the same approach that the oxer cited earlier. The difference was that the jump was bigger. It was a spa which dimensions were at the maximum authorized. The difficulty was that we were asked to jump the spa in the wrong direction. A spa is usually composed of three or more poles placed in a progressively high position. The norm is to approach the jump from the lower pole. The course designer had the strange idea to make the obstacle more challenging, asking us to approach and jump the spa from the higher pole's side. I did not accelerate in the turn, thinking that an oblique trajectory would make the width beyond Quolibet's capacities. I guess, Quolibet felt that the lack of momentum was beyond his limits, and he refused the jump. The refusal permitted us to try again from a different angle with more momentum. Quolibet considered that the performance was now within his limits, and he flew over the spa without hesitation.

"An intellectual is a man who takes more words than necessary to tell more than he knows." (Dwight D. Eisenhower) Often, the equestrian world intellectuals criticized the fact that I was carefully rebalancing Quolibet in front of the jumps. According to these great thinkers but little achievers, I was losing precious seconds. Quolibet's comfort zone was proper balance and proper placement of the take-off stride. He had great stamina and preferred to canter faster between the jumps than being rushed in the jump's proximity. The extreme difficulty of Punchestown's cross country course was a significant reason behind Quolibet's success.

Once in a while, in the history of a three-day event, a jumping course reaches maximum difficulty level causing numerous injuries to both the horses and the riders. The cross-country course of the Punchestown world championship was beyond reasonable limits. The consensus was that the course designer was virtually drunk when he designed the course. We were thirty-two riders participating in the event, and the total of falls exceeded sixty. Quolibet and I ended the cross country course with one fall and one refusal, which was the French squad's second-best performance. Considering that only two teams finished the event, The British, which won the gold medal, and the French, which gained the silver medal, one can measure the course's difficulty level. The problem was not to finish fast but instead to finish with minimum issues. Speed being no longer a factor, I carefully balanced and placed the take-off for each jump, and Quolibet had the guts to resolve all the problems.

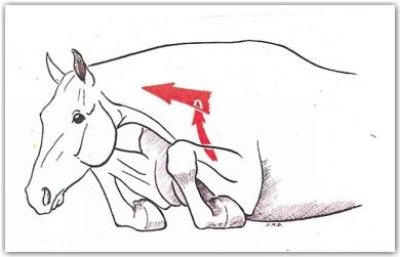

The fall was not Quolibet's fault. It was a sharp hill down, and a small ridge was built in the middle. The ridge barely gave enough room for the horse's four feet. The horse was supposed to take off from the ridge and jump a pole attached between two trees. The landing was then six feet lower. Quolibet's right front foot tripped on the ridge's edge, and he crashed chess first onto the pole. He flipped over, describing a summersault, and we both rolled down the hill. He stood up before me and was immediately held by the British rider Marc Phillip, who is now coaching the American three-day event team. As I stood up, really not knowing where I was, another member of the British team named Richard Meade gave me a leg up to put me back on the horse. Realizing that I was not aware, Richard Meade also told me the right direction for the next jump. A three-day event is definitively the equestrian discipline where fairness between competitors was and still is the greatest. At the time of the incident, both Richard Meade and Marc Phillip knew that the final decision would be between the British and the French team. Even if I was in competition with them, they did not hesitate a second helping me.

The next jump was the more difficult question of the course. It was a humongous oxer with a six-foot drop on the other side. I launched Quolibet at maximum speed, thinking that the previous fall may have impressed him. I was anticipating that he might hesitate at the last second. Once again, I was wrong. He came on the jump full speed taking off without even a suspicion of fear. As a result, the landing was quite intense. We barely made the right turn after the landing. My left foot knocked on the tower on which a camera of the BBC was installed. The story was that the impact shook the camera, and the picture disappeared for a few seconds. My teammates who watched my progression through the course on the TV monitor wondered if Quolibet and I had survived the impact.

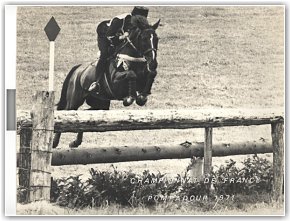

A picture taken at the landing demonstrated the human tendency to find arguments accrediting preconceived opinions. I showed poor judgment, thinking that Quolibet might be impressed by his recent crash and consequently created the conditions for a difficult landing. The impact force was quite intense, and I guess the attraction of gravity pulled my heels down. A photographer took a picture at the instant of impact, and the image was published in an equestrian magazine as an example of classical equitation. The legend below the picture was, "even at the landing of the most difficult obstacle, the rider keeps the heels down."

Jean Luc Cornille Science Of Motion |