The bridle-less cross country course

The bridle-less cross country course Copyright©2010

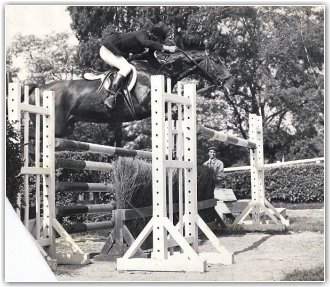

(photo is of Atoll in jumping class)

Jean Luc Cornille

The event was an International Three Day Event in Deutschland. The horse was a Selle Francais named Atoll II. The story is that I finished the cross-country course without a bridle. This was not a voluntary situation. Atoll was a great jumper, but he was also unstoppable on the cross country course. He was unstoppable in every sense of the term. He never had a refusal on a cross country jump during his entire career, but he was also very difficult to slow down or rebalance between the jumps.

The first element of the water jump was a four feet vertical landing into the water. It was about six canter strides in the water, and the exit was another vertical. I entered the combination too fast, and the braking effect of the water compromised the horse balance. Even if the water level was not very deep, we both virtually disappeared under the water, re-emerging like a submarine one or two strides later. The water was not very tasty, but even less tasty was the fact that the reins were no longer on the horse’s neck. In fact, the bridle was no longer on the horse’s head either. The whole tack has been pulled out by the impact force and was now somewhere at the bottom of the water complex. Atoll was now bridleless.

Atoll enjoyed his freedom. He cantered through the water, jumping the second vertical better than he would have done if I had attempted to control him. We were at this point relatively close to the finish line. It was a left turn toward a combination and a straight line until the finish line. I applied pressure on the horse’s neck with my hands, hoping that Atoll will turn, and he did without hesitation. The combination was a series of four efforts. It started with a jump over a bank. It was then a bounce over a vertical, followed by one stride on the bank. The combination finished with a drop from the bank and a bounce over the last vertical. Atoll negotiated the combination perfectly well and cantered full speed toward the finish line. Atoll continued then at the canter.

Teammates and others who had realized the situation were lifting their arms, hoping to slow down the horse. Atoll responded, turning in a circle but was not willing to slow down. At this time, it was a weight regulation in the three-day event. The rider had to weigh 75 kilograms with or without the saddle. Once passed the finish line, the rider had to be weighted on a bascule, and it was a time limit. I needed the saddle to satisfy the weight requirement.

As Atoll remained at the canter on the circle, I realized that he might canter longer than the authorized time. My thought was to remove the saddle and jump off the horse. I attempted to bend over to reach the girth, but feeling my body leaning forward, Atoll accelerated the pace. I decided then to jump off the horse, hoping that I could run next to him and unbuckle the saddle. In fact, it turned to be easier than I anticipated. Atoll slowed down to the walk as soon as he felt that I was no longer on board. I was then capable of unbuckling the girth, removing the saddle, and running as fast as I could toward the bascule with the saddle on my arm. I sit on the bascule only a few seconds before elimination.

The funny point is that the three-day event regulation did not envision at this time that a horse could finish a cross-country course without a bridle. It was specified that the horse must finish the course at the canter. It was requested that the rider weighed 75 kilograms with or without the saddle, but nothing about the bridle. Atoll performance was, therefore, valid.

No need to say that for months comments and jokes abounded from everyone. Some pointed out that the horse was much better when I was not interfering. Others suggested that my riding style, which was fast with the horse on long reins, had become better than ever. Jean Luc