Mechanoresponsivenss 35

Mechanoresponsiveness 35

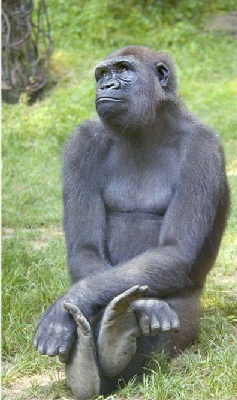

Waiting for the emergence of the human intelligence.

We cannot take a break from knowledge. Either we progress, either we regress. Even a curator of the museum has to learn new techniques preserving more efficiently the treasures of our ancestors. However, once a painting or a sculpture is completed, we can appreciate it, wonder about the artist’s talent. We can preserve it, but we cannot improve it. The greatness of the equestrian art is that knowledge constantly evolves, furthering endlessly the art of developing and coordinating the horse physique for the athletic demand of the performance.

“I believe that there are two categories of ecuyers, those who, while skilled, use the horse as a tool, and those who love him and allow him to express the brilliance of which he is capable.” (Nuno Oliviera) In Nuno’s mind, the ones who love the horse takes the risk of lightness even if the ones holding the reins firmly, are more likely to win a ribbon. Classical literature regards lightness as a more ethical form of equitation. Equine science exposes lightness as the only form of equitation allowing precise coordinating the horse’s physique for the move.

Literature and science sometime meet, often separate. They refer to the same horse but literature rests essentially on visual impression and rider’s perception. Science, instead, studies the horse from gross anatomy to molecular level providing the essence of the equestrian art. "Descriptions related to collection have been the subjects of many publications in which the Masters described through their doctrine, the consequences and causes of collection in order to develop a riding technique. Such riding technique rests essentially on visual observations and rider's perceptions leading to affirmation which never have been scientifically demonstrated." (Sophie Biau, 2003 PhD Thesis) As knowledge deepens, the equestrian art supported by modern science evolved into another world, even if, paraphrasing William Butler Teats, this other world is in this world. “There is another world, but it is in this one.” (William Butler Yeats)

Classical literature does not talk about tensegrity, but tensegrity is holding life together. Classical literature ignores elastic energy, but elastic energy is the power and the spirit of the equestrian art. Classical literature skips the concept of mechanoregulation but mechanical forces are sculpting life from cells specialization to the stability of the horse’s joints and vertebral structure. .“Experiments with cultured cells confirm that mechanical stresses can directly alter many cellular processes, including signal transduction, gene expression, growth, differentiation, and survival.” (Christopher S. Chen and Donald E. Ingber.

Stephen Levin, describes how every part of an organism from molecular to gross anatomy, is integrated by a mechanical system into a complete functional unit. Fascia for instance, is arranged in sleeves wrapping joints and keeping bones apart as they flex. Under tension, fascia is strong enough to maintain the integrity of the joints and augment muscular work. Fascia is keep under tension by muscles and mechanical forces. Without the facia under tension, the joints would not be able to absorb impact and other forces involved in locomotion and performances; the cartilages would be destroyed.

Classical literature teaches how to make the horse do it. Science explains how the horse does it. Quite often, conclusions based on visual impression and feeling are not even close from actual functioning of the equine physique. At the 18th century, François Robichon de la Gueriniere talked about improving the art with the help of science. Three centuries later, there is no equestrian art without upgrading classical thoughts to actual science, unless, one considers that making a dysfunctional athlete executing movements out of his talent until pathological damages end his career, is an art.

The equestrian art is evolving from the subtle submission to the rider’s aids, to a sophisticated partnership with the horse’s intelligence. Tensegrity, elastic energy, mechanoregulation, cannot be stimulated by the rider’s aids. They have to be processed by the horse’s brain. The horse’s education is about, creating conditions guiding the horse brain toward proper tensegrity, greater use of elastic energy and regulation of mechanical stress. The load of the forelegs for instance, can be reduced slowing the horse cadence to his natural frequency and educating back muscles in converting the thrust generated by the hind legs into greater upward forces. stimulating the horse’s brain. “An initial thrust on the column is translated into a series of predominantly vertical and horizontal forces which diminish progressively as they pass from one vertebrae to the next”. (Richard Tucker, Contribution to the Biomechanics of the vertebral Column, Acta Thoeriologica, VOL. IX, 13: 171-192, BIALOWIEZA, 30. XL. 1964).

“Those who know, do. Those who understand, teach.” (Aristotle) Teaching the horse demands understanding tensegrity, elastic energy, mechanoregulation, and creating situations allowing the horse’s brain to process efficient muscle work and body coordination. Teaching, is analyzing the horse’s processing, including errors. Errors are gifts describing in which direction the horse mind is actually thinking and which insight could direct the horse mind toward the proper body coordination. Efficiency is ease, effortlessness and soundness.

Most riders have the intelligence of working with the horse’s intelligence. Horses definitively do, even if, quite often, they have to wait a long time, for the emergence of our intelligence. Riding is physics, energy, tensegrity, elastic energy, forces and leading the horse to mastery of forces is an intelligent journey. Decades ago. It was already known that elastic energy was a great part of locomotion. “The elastic energy stored in and recovered from tendons during cyclical locomotion can reduce the metabolic cost of locomotion.” (Cavagna et al., 1977Go; Alexander, 1988Go; Roberts et al., 1997) It was later explained that, within muscles, microscopic filaments referred to as filament titine, were major components in muscle elasticity and spring capacity. “Titine functions as serially linked spring that develop tension when stretched. There are multiple titin isoforms that vary in size and stiffness. Which explain the elastic-stiffness diversity across vertebrate muscles.” (Paul C. LaStayo, PT, PhD. John M. Woolf, PT, MS, ATC. Michael D. Lewek, PT. Lynn Snyde-Mackler, PT, ScD. Trugo Relch, BS. Stan L. Lindstedt, PhD. Journal of Orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 557-571. Volume 33, NUMBER 10, October 2003)

As understanding deepened, the concept of frequency or cadence became a fundamental component of the picture, as within the muscle’ belly, filaments and cells have to be tuned to the stride frequency. “If titine is functioning as a locomotor spring, then it should be tuned to the frequency of muscle use.” More recently, Stephen Levin and others describes how every part of an organism from molecular to the gross anatomy, is integrated by a mechanical system into a complete functional unit. When under tension, fascia is a great part of the system stabilizing joints and assisting and augmenting muscle function. Tensegrity Is the best explanation for how bodies stay intact and handle variable load. Storage and reuse of elastic energy is the essence of efficient gaits and athletic performances. Through their ability of converting the thrust generated by the hind legs into upward forces, back muscles have the capacity to regulate mechanical stress loading the limbs and other structure.

Compared to the primitive theories of submission and obedience to the rider’s aids, the real components of sound gaits and athletic performances appears impossible to control. They are indeed impossible to control, but they are easy to influence through partnership with the horse’s intelligence.

Education is teaching the brain to think. Educating a horse is teaching the horse brain to think. A simple example known as stretch-shorten contraction, might help understanding how we can teach the horse’s brain to think in terms of efficiency. When a muscles contract and is simultaneously elongated by an external force, the contraction is referred to as eccentric contraction. Eccentric contraction is also referred to as, “active stretching”. This is when the greatest magnitude of force occurs. Eccentric contraction is often labeled as high-power contraction. During different sequences of the stride, many muscles work eccentrically storing elastic strain energy. During the cycle of locomotion of a horse working at his natural frequency or cadence, eccentric contraction is often immediately followed by a concentric contraction. When the frequency is correct, the elastic strain energy stored in the muscle, during the eccentric contraction, reduces the work of the following concentric contraction. “The ability of the muscle-tendon units to recover elastic strain energy is apparently energetically so advantageous that the most economical stride frequency in running may be set by this key component alone.” (Paul C. LaStayo, PT, PhD. John M. Woolf, PT, MS, ATC. Michael D. Lewek, PT. Lynn Snyde-Mackler, PT, ScD. Trugo Relch, BS. Stan L. Lindstedt, PhD. Eccentric Muscle Contractions: Their contribution to injury) The horse is then capable to sustain a springy and rhythmic trot increasing storage and reuse of elastic strain energy, minimizing muscular work.

In the science of motion, we refer to this springy, light and effortless trot as the Pignot Jog, in memory of a steeple chase trainer, named Rene Pignot. Intuitively Pignot discovered in the late sixties that it was a cadence, lightness on the bit and balance where the horse trotted bouncing their strides effortlessly. Pignot did not know biomechanically how the horse did it but he observed that he increased his horses muscle mass, power and elasticity practicing long sequences at this rhythmic trot. He prepared his steeple chase horses this way and, applying his findings, I prepared my three-day event horse the same way. I also observed gain in calmness as the horses developed the muscle mass allowing them to deal with their nervous influx.

When the scientific explanation became available, the stretch-shorten contraction phenomenon, the calmness that I referred to as “intelligent calmness,” opened new perspectives. As the horses trotted effortlessly, and therefore at ease, they started taking initiatives finding the right cadence, balance and lightness by their own. They could not do it without the rider’s help but they were actively interested in the search. They engaged their brain exploring different adjustments leading to effortlessness. This observation leads me to wonder if they would use their intelligence in search of ease and effortlessness if the study of movement was no longer focusing on superficial appearance, but instead, developing and coordinating their body for the athletic demand of the move. The horses’ reactions were both astounding and sad. They were capable and interested in refining subtle coordination, far beyond the scope of natural reflexes. It was sad realizing that all these previous years, they have patiently supported my equitation of gestures, hands action, legs actions, shift of body weight, waiting for the emergence of my intelligence.

Jean Luc Cornille

twitter

twitter facebook

facebook google

google pinterest

pinterest linkedin

linkedin