Lateral bending and transversal rotation

Response to the waspish ghosts of theological thinking.

(IX)

Lateral bending and transversal rotation

Part 2

In response to an extensive reaction on facebook, we are furthering the discussion about transversal rotation. We are amazed by the fact that the phenomenon was, until we published it, foreign to most riders and trainers. Without a sound understanding of the rotation associated with lateral bending there is no way to properly ride or train the shoulder in or the half pass or the flying change. Collection in front of a jump as well as the ability to turn sharply at the landing is related to the horse’s ability to properly coordinate lateral bending and transversal rotation. In terms of therapy, the phenomenon is even more important. All the cases of kissing spine that we have rehabilitated were for a great part the result of inverted rotation. I guess a few skilled riders have intuitively figured out the correlation without been able to explain it. Undoubtedly, a very large number of talented riders could have furthered their horse’s performances, encountered much less difficulties, and prevented injuries if the knowledge had been made available to them.

The most comprehensive study is certainly the work of Jean Marie Denoix, which has been published in 1999 (1). However, the presence of transversal rotations in the horse’s vertebral column was already reported in 1964. “Transversal forces are permanent components of the work of the vertebral column and are resisted by the strong development of the articular processes of the vertebrae. For this reason, they are strongly developed in terrestrial mammals but reduce or absent in fish where gravitational forces are unimportant.” (2)

The thought that the ribs are part of the mechanism resisting gravity forces is now the subject of renewed interest. Recent observations in different necropsy rooms have noticed bony developments on the upper end of the ribs where the processes are articulated with the vertebrae. The deposits appear to be responding to stresses. There is not yet a clear explanation but several pathologists, include Dr. Betsy Uhl who is going to give a talk at our November Immersion Program, are working on the observation.

Tucker completed in 1964, the first dynamic analysis of the horse’s vertebral column. Beside the presence of transversal forces, Polish scientists demonstrated that forward movements and performances were not created through relaxation of the back muscles and greater amplitude of the vertebral column movement, but through resistance of the back muscles which maintains the movements of the thoracolumbar spine within the limits of its possible range of motion. “Since all movements have a rotary action, the vertebral column is constantly subjected to rotary forces. These are applied to each of the vertebral components of the column and it is the constant task of the epaxial musculature to counteract the effects of these rotational forces”(3) Without this understanding, a rider cannot efficiently influence and modify these transversal rotations. Astoundingly, judging standards, most training techniques, and forums on the internet, are still promoting relaxed and swinging motions of the horse’s vertebral column.

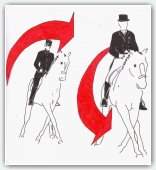

On this picture,  left lateral bending is coupled with proper rotation, (left side of the picture), and inverted rotation, (right side of the picture).

left lateral bending is coupled with proper rotation, (left side of the picture), and inverted rotation, (right side of the picture).

We place then a rider’s skeleton on a horse combining left lateral bending and inverted rotation. The rider’s skeleton is then shifted toward the outside of the bend.

Dressing the skeleton into a modern rider exposes even further the visual impression created by inverted rotation.

The female rider on right side illustrates the direction of the inverted rotation shifting the rider toward the outside of the bend. By comparison the silhouette on the left side of the picture illustrates half pass combining left later bending and correct rotation.

Judges are not trained to distinguish correct from inverted rotation. Therefore, judging standards reward indiscriminately a dysfunctional athlete and a properly trained horse. The difference is that the dysfunctional horse will have to have most of the cartilage of his body regularly injected while the horse properly coordinated will remain drug free and sound.

Lateral bending as well as transversal rotations occurs mostly between the 9th and 14th thoracic vertebrae, which is exactly between the rider’s upper thighs. The rider’s pelvis and thighs are therefore at the best place to create lateral bending of the horse’s thoracic spine associated with correct rotation. However, concepts such as the driving seat do not permit proper control of the horse’s thoracolumbar spine. There is no doubt that the waspish ghosts of theological thinking are now exchanging frantic e-mails convincing themselves that their deep seat is right and my lines are wrong. This is why ghosts will always remain ghosts. They cannot be wrong and therefore, they cannot evolve. Their so-called in depth discussions are in fact diatribes around elementary details quickly turning into an anthology to their incommensurable ego.

We place the ghost picture on the right side of the page,  so hopefully, the horse’s momentum will pull him or her out of the picture and we can continue this discussion between real riders. The main back muscles are set in mirror image directions and therefore, any shift of the rider’s weight is disturbing the horse’s ability to synchronize the work of his back muscles. Back and forth oscillations of the rider’s pelvis in the saddle are creating serious weight disturbances, shifting the rider’s weight back to front and front to back. Efficient equitation commences with a stable pelvis.

so hopefully, the horse’s momentum will pull him or her out of the picture and we can continue this discussion between real riders. The main back muscles are set in mirror image directions and therefore, any shift of the rider’s weight is disturbing the horse’s ability to synchronize the work of his back muscles. Back and forth oscillations of the rider’s pelvis in the saddle are creating serious weight disturbances, shifting the rider’s weight back to front and front to back. Efficient equitation commences with a stable pelvis.

The concept of a stable pelvis is not new. In the 17th century, Duke William Cavendish of Newcastle (1593-1676) promoted the need for a stable pelvis and upper thighs. The British gentleman even uses the term “immovable” pelvis. “A rider’s body should be divided in three parts, two of which are mobile and one which is not. The first of the two movable parts is the body down to the waist; the other is the leg from the knee downward. Therefore, the immovable part of the body is from the waist to the knees.” Newcastle did not know that the horse’s back muscles were arranged in opposite directions but he had enough feeling and intuition to realize that shifts of the rider’s weight were hampering the horse’s ability to control balance.

The first description of the main back muscles was made in 1946 by the Dutch scientist E. J. Slijper. This illustration is copied from Slijper’s book, Comparative biologic-anatomical investigations on the vertebral column and spinal musculature of Mammals. As today, only 18 books remain in circulation in the world and we have been lucky enough to copy one of them. Slijper only describes in this illustration the design of the longissimus dorsi muscles. Instead of long bungee cords, as often described, the longissimus dorsi are in fact several muscles aligned in line and composed of fascicles oriented forward and downward. The fascicles bridge about 3 to 5 vertebrae. By contrast, the fascicles of the multifidius muscles are oriented in the opposite direction, and therefore backward and downward. One can visualize the opposite orientation of the main back muscles on this picture. The fascicles of the longissimus system are illustrated in red while the fascicles of the multifidius muscles are represented in green.

As today, only 18 books remain in circulation in the world and we have been lucky enough to copy one of them. Slijper only describes in this illustration the design of the longissimus dorsi muscles. Instead of long bungee cords, as often described, the longissimus dorsi are in fact several muscles aligned in line and composed of fascicles oriented forward and downward. The fascicles bridge about 3 to 5 vertebrae. By contrast, the fascicles of the multifidius muscles are oriented in the opposite direction, and therefore backward and downward. One can visualize the opposite orientation of the main back muscles on this picture. The fascicles of the longissimus system are illustrated in red while the fascicles of the multifidius muscles are represented in green.

However, in reality the muscles are very thick and difficult to distinguish. Illustrations always present a clean and sterile picture. The reality is more complex. The perspective given in the necropsy room is that these muscles are so deeply interrelated that it would be impossible to discriminate them, or to act separately on one without influencing the other. The second impression is that the movements of the horse’s vertebral column are even less than experimental measurements like to suggest. The reason is that measurements are executed when all the back muscles have been removed.

The point is that since the main back muscles are set and act in opposite directions, any shift of the rider’s weight will stimulate one muscle group over the other. The problem is that the muscular coordination allowing the horse to resist gravity and consequently to control balance, demands a precise and simultaneous work of both muscles’ group. Newcastle was right when he advised an immovable pelvis. By contrast, in the matter of back muscles and proper work of the biomechanics of the horse’s vertebral column, principles of modern riding emphasizing relaxation and therefore large oscillations of the rider’s back are off. Back and forth oscillations of the rider’s pelvis induce forces acting back to front and front to back on the horse’s back muscles. These forces are altering the horse’s ability to properly coordinate the work of his back muscles.

In fact, both the French and the German schools are pushing with the seat, which is questionable in the light of actual knowledge of the horse’s back muscles structure. With his immovable pelvis, Newcastle was closer to actual knowledge of the equine physiology than are contemporary schools of thought. The French school is about lightness on the bit. The German school emphasizes firmer contact. Great riders of both schools are not pulling back on the reins. They might resist and eventually filter the weight exerted by the horse on the bit but they do not pull backward on the reins. Instead, bad riders do, applying to the letter the sally “push and pull.”

In order to efficiently influence lateral bending of the horse’s thoracolumbar spine, the rider needs to be in neutral balance, which means that the rider needs to be exactly vertical over his or her seat bones. Of course, since the seat bones are only offering two points of support, the gluteus muscles of the fannies and the inward muscles of the upper thighs are involved, stabilizing the rider’s seat. The alignment of the rider’s vertebral column is equally important. The S curve of the rider’s spine needs to be held as straight as it is physically comfortable for the rider to hold it. The S shape of the rider’s spine will remains an S shape but closer to a straight line than a pronounced S shape. The best description of the rider’s vertebral column alignment and functioning belongs to Valdemar Seunig. “The subtle S-curve of the spine allows the spine to oscillate minutely, a movement so tiny that it is hardly perceptible to the naked eye, producing a “soft” seat. This “soft seat” differs fundamentally from a “doughy” seat, in which we find a spine that is too flexible and allowed to undulate freely in response to the horse’s movement.” The art of riding, which is the rider’s ability to prepare efficiently the horse’s physique for the athletic demand of the performance, does not belong to the German school over the French and vice versa but instead to the understanding of the best riders’ findings in the light of actual knowledge of the equine physiology.

Above all, there is a dynamic phenomenon, which can be defined as the center of rotation and that needs to be addressed. The rider can have the shoulders at the vertical of the seat bones but collapsing the vertebral column backward, or holding the vertebral column too arched as hunter jumper riders tend to do. Both forms of equitation hamper the horse’s ability to master balance control. Collapsing the vertebral column backward as in a bracing position is inducing a force acting back to front on the horse’s back muscles. By contrast, arching the back excessively is inducing a force acting front to back on the horse’s back muscles. In both cases, the influence of the rider’s weight is complicating the horse’s task, which is precise coordination and simultaneous work of muscles set in opposite direction.

To understand the concept of the center of rotation, one may watch a cat falling.  The cat creates a center of rotation in the middle of his spine around which the cat turns the front and back part of his body and lands on his legs. The junction between the natural kyphosis of the rider’s thoracic spine and the natural lordosis of the rider’s lumbar vertebrae can be considered as an axis of rotation around which the rider articulates his or her vertebral column. For example, if the rider flattens the lumbar vertebrae using the spaos muscles, compensation needs to be made advancing slightly the thoracic vertebrae between the shoulder blades. Acting this way, the rider is capable of constantly maintaining the center of rotation of his or her spine exactly at the vertical of the seat bones. This allows a real neutral balance, which means a body weight acting vertically on the horse’s spine and therefore avoiding all nuisances caused by a body weight acting front to back or back to front.

The cat creates a center of rotation in the middle of his spine around which the cat turns the front and back part of his body and lands on his legs. The junction between the natural kyphosis of the rider’s thoracic spine and the natural lordosis of the rider’s lumbar vertebrae can be considered as an axis of rotation around which the rider articulates his or her vertebral column. For example, if the rider flattens the lumbar vertebrae using the spaos muscles, compensation needs to be made advancing slightly the thoracic vertebrae between the shoulder blades. Acting this way, the rider is capable of constantly maintaining the center of rotation of his or her spine exactly at the vertical of the seat bones. This allows a real neutral balance, which means a body weight acting vertically on the horse’s spine and therefore avoiding all nuisances caused by a body weight acting front to back or back to front.

Theologians are going to object vehemently because they know the words but they have not pushed their equitation or their understanding of the equine physiology very far. The practical application of knowledge is not about words but instead, riding skill, feeling, extensive experience, and an absolute desire to educate the horse as efficiently as knowledge permits instead of submitting the horse to a doctrine. Interestingly, as I was evolving in my own equitation, the French school was considering that I had a very classical French seat and the first thing German riders told me when I went to Germany to understand the German approach, was that I had a German seatů

Influencing lateral bending and transversal rotation of the horse’s thoracolumbar column is very easy. One simply has to face right with the pelvis and upper body in order to bend the horse’s thoracic spine to the right, or facing left with the pelvis and upper body in order to bend the horse’s thoracic vertebrae to the left. For instance, as the rider’s pelvis, back and shoulders are facing right, the rider’s inside leg is acting as a reference around which the horse is bending the spine. The reference of the rider’s inside leg is mostly created by the contact of the inward upper thigh on the saddle and the calf touching the horse’s body.

However, without a seat exactly in balance over the seat bones, the technique does not work. Both sides of the rider’s back, the pelvis and the inward upper thighs need to work together. The horse does feel the rotation of the pelvis through the light pressure exerted by the outside thigh on the saddle. The rider’s rotation induces transversal rotation of the horse’s dorsal spine toward the inside of the bend, which produces lateral bending. “In the cervical and thoracic vertebral column, rotation is always coupled with lateroflexion and vice versa. In the thoracic spine, as is the case during lateroflexion, the spinous processes bend in the concavity.”(4) Efficient equitation is not about submitting the horse to the rider’s aids but instead, proper riding is about inviting the horse to dance. The first condition is evidently to dance the same dance.

Prior this knowledge, riding principles emphasized the thought that advancing the rider’s inside hip toward he horse’s vertebral column would induces lateral bending of the horse’s thoracic spine around the rider’s inside hip. This theory is no longer acceptable since the move stimulates a rotation toward the outside of the bend and therefore, inverted rotation. Dancing the same dance, commences with a sound understanding of the horse locomotion.

The study of biomechanics is about understanding how forces interact and stress the structures. When two biomechanical entities, the horse and the rider, are working together, obedience to the rider’s aids is almost an insult to the intelligence of both, the horse and the rider. Efficient equitation occurs at a much more sophisticated level. If the rider is using his or her physique in respect of proper functioning of the horse’s physique, there is no resistance from the horse. There might be faults or difficulties which result from the horse’s muscular imbalance, weaknesses or inadequate body coordination. It belongs then to the rider’s analytic capacities to figure the root cause.

If the rider is properly balanced over the seat bones, if the rider’s weight distribution is equal on both seat bones, turning the back, pelvis and thighs to the right invites the horse to bend the thoracic spine to the right. This is not submission, this is dance. The horse bends the thoracic spine simply because like the rider, the horse likes to move in harmony. Instead, if the rider is seat mostly on his or her gluteus muscles loading the back part of the saddle and holding the knees against humongous knee pads, the rotation of the pelvis induce a series of weight shifts that are totally incomprehensive for the horse. For instance, if the rider is seat too far back on the fannies, the rotation of the pelvis to the right demands an elevation of the left hip and therefore a loading of the right seat bone which pushes the rotation of the horse’s thoracic spine toward the outside of the bend. The rider stimulates then inverted rotation. Showing ignorance of the vertebral column mechanism, there are school of thoughts which emphasize loading the inside seat bone.

Basically, the rider influences the horse’s thoracic spine with the seat and the cervical spine, the neck, with the hands. Lateral bending of the thoracic spine can easily be disturbed by excessive bending of the neck. The so-called safety rein, which was referred to at the beginning of this discussion, emphasizes intense lateral bending of the neck. This form of riding is about submitting the horse to cues without the most elementary understanding of the horse’s locomotor system and vertebral column mechanism. In the same line of severe ignorance are training systems emphasizing bending the horse’s thoracolumbar spine through bending of the neck.

It is obvious that if the horse has been educated through old theories or rein effects, significant asymmetries between right and left side may already exist. In such case, the horse may respond easily to the rider’s suggestion on one side and have more difficultly, or do not respond at all on the other side. Appropriated re-education is necessary. This cannot be treated in two lines. It is the subject of another installment. This is also a subject of the Immersion Programs that we are running at the Science of Motion’s training center. The programs are designed to provide advanced knowledge of the equine physiology and how to apply such knowledge. The first aim is to give to the rider the capacity to discriminate theories unrelated to the horse’s biological mechanism and working hypothesis respecting the horse’s physique.

Jean Luc Cornille

Copyright©2011 All rights reserved

Sign up for our free newsletter Drowning the fish.

References,

-(1) (4) (Spinal Biomechanics and Functional Anatomy, 1999)

-(2) (3)(Richard Tucker, Biomechanical Characteristics of the thoraco-lumbar Curvature. ACTA THEORIOLOGICA. Vol. VIII, 3: 45-72, Bialowieza, 15.X.1964)

twitter

twitter facebook

facebook digg

digg google

google stumbleupon

stumbleupon yahoo

yahoo newsvine

newsvine reddit

reddit linkedin

linkedin blogger

blogger