Mechanoresponsiveness 29

Mechanoresponsiveness 29

Stretch your imagination; not your horse

Jean Luc Cornille

The construction of a bridge demands ingenious architecture allowing simultaneously, strength and lightness. For this purpose, the concept of tensegrity is abundantly used.” A tensegrity structure is characterized by use of continuous tension and local compression.” (Christopher S. Chen and Donald E. Ingber. Tensegrity and mechanoregulation: from skeleton to cytoskeleton, 1999) The horse is a tensegrity expert. From simple joints which are stabilized by continuous balance between tension and compression elements, down to microscopic level, where contractile microfilaments and microtubules act as balanced tension and compression elements respectively, tensegrity is one of the techniques allowing the horse to combine strength and lightness.

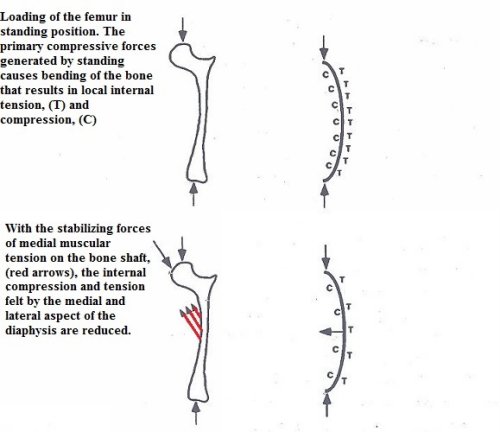

For speed, jumping and other performances, the horse lower legs have to be light and yet capable to withstand considerable impact forces. For this reason, joints are reinforced by tendons and associated muscles. Without the support of the tendons and appropriated contraction of the associated muscles, the joints would not be capable to support the considerable stress induced during impact and the whole stance. The whole horse locomotor system functions under the principle of contraction, compensatory contraction, stabilization, forces transport, which all require nuances in muscle tone but not lack of muscle tone. Concepts of stretching, relaxing and releasing muscles, are simplistic and even, in some instances damaging. Standing still, and never the less in motion, the femur for instance bends under the load. The internal structure of the bone is designed to deal with tension and compression, but muscles are also part of the stability, releasing these muscles weakens the stability of the system.

Releasing these muscles, (red arrows) compromise the systems allowing the bone to withstand forces.

Muscles are doing a lot more than contracting and stretching. A muscle covering several joints can absorb power at one joint and simultaneously produce power at another joint. “This function of biarticular muscles is referred to as power transport between joints”. (Gregoire and al., 1984) Tendons can also transport power. All this sophisticated system is part of efficient and sound locomotion. Amplitude in locomotion and performance is not achieved elongating muscles. Amplitude is mainly created through the recoil of elastic strain energy stored n tendons, aponeurosis, muscles during the decelerating phase of the stride and reused for the propulsive phase and the swing. Elasticity in muscles has a lot more to do with the cytoskeletal protein named ligament “titine” than stretching and elongating muscles.

Titine are filaments within the muscles that increase tension when elongated. There is a great diversity of elastic-stiffness in muscles which is due to multiple “titine” isoforms that vary in size and stiffness. The concept of elastic stiffness is a fundamental principle of locomotion. A spring stores strain energy when elongated and restitutes the energy when returning to its normal length. The density of the structure resist strain, storing energy. A weak spring does not store much energy. A bungee cord stores elastic strain energy when elongated and restitutes the energy when returning to its initial length. A weak elastic does not store much energy. Tendons, ligaments, aponeurosis, muscles work under the principle of storage and reuse of elastic strain energy.

Titine functions as a locomotor spring that has to be tuned to the frequency of the muscle use. Understanding and respecting the horse’s frequency is much more likely to develop and increase muscles elasticity than stretching and relaxation. “In a sense, because the muscle is composed of both muscle fibers and tendinous materials, all of these structures must be collectively ‘tuned’ to the spring properties for the muscle-tendon system to store and recover elastic strain energy during locomotion.” (Paul C. LaStayo, PT, PhD. John M. Woolf, PT, MS, ATC. Michael D. Lewek, PT. Lynn Snyde-Mackler, PT, ScD. Trugo Relch, BS. Stan L. Lindstedt, PhD. Journal of Orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 557-571. Volume 33, NUMBER 10, October 2003)

Frequency or cadence, are generic terms describing a network of numerous oscillations and vibrations. “A given multicellular organism (like a person) is a collection of many different oscillations and vibrations (Hertz is cycles per second, and our body operates on many different cycles per [time period]--heart rhythm, breathing, brain waves, blood pressure, etc), many of which are out of our control (and some of which you don't WANT to change... like the Q-T segment of a heartbeat!).” (Leslie Ordal Clinical research manager in a neuroscience-based rehabilitation lab,) Respecting the horse frequency is a perquisite for efficiency and soundness. Each horse does have his own cadence and no sound education can be made rushing the horse at a frequency exceeding his natural cadence.

Speed is created stiffening the back muscles and rushing the horse at a speed greater than his natural cadence stiffens the back muscles. Trying to release the stiffness of the back muscles through stretching and relaxation is an oxymoron. Sound education demands instead, and within each gait, respecting the horse natural cadence and tune the rhythm of the rider actions to the horse frequency. “Furthermore, muscle force can only increase and decrease gradually, muscles cannot be either ‘on’ or ‘off’ momentarily.” (Liduin S. Meerrshoek and Anton J. van den Bogert. Mechanical nalysis of locomotion, 2003)

“The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination.” (Albert Einstein) Especially when imagination rises from knowledge. The aim of academic equitation is no longer, restoring to the mounted horse the gracefulness of movement which is possessed when he was free but becomes marred by the rider’s weight and movements. (Academic Equitation, 1949) The aim of academic equitation is creating the body coordination preparing optimally the horse physique for the athletic demand of the performance. Even for the simplest performance, carrying a rider through the country side, the horse has to increase the duration of the decelerating phase storing more energy for the pushing phase and the swing. “It should be borne in mind that the weight of the rider will rise two- or three-fold during locomotion and also that more energy is required by a mounted horse and this energy must be obtained by increasing the stance phase so as to recover more energy during the swing.” (J. L. Morales, DVM, PhD, 1998)

The problem is that a horse executes gaits and performances protecting whatever morphological flaw, muscle imbalance or other issue altering the horse body at the instant of the demand. Idealistically, a horse should react to the rider weight increasing the duration of the hind legs decelerating phase. Very often, the horse brain reacts to the load of the rider body protecting or aggravating existing muscle imbalance or other issue. During piaff for instance, the hind legs develop a considerable decelerating activity preventing forward shift of the body over the forelegs. At a lesser level, the decelerating phase of the hind legs is part of the coordination allowing the horse to control balance. This does not occur during the propulsive phase as our ancestors believed. Without technologies measuring forces, our ancestors had to resort to the naked eye or even photographic series, such as the beautiful work of Edward Muybridge, which does not permit to distinguish the two consecutive phases, the braking or decelerating phase and the pushing phase, that occur during the stance. Without advanced technology, it was logical to think that the hind legs propelled the horse body upward and forward as soon as ground contact. It was naïve and inaccurate but it was logical; exactly like it is logical to believe that the antidote for muscle contraction is relaxation. It is logical but it is inexact. A horse does not function at the level of stretching and relaxation but instead at the level of nuances in muscle tone. The antidote for contraction is not relaxation; the antidote for spasm and contraction is proper and subtle orchestration of contraction, compensatory contraction, stabilization, force transport and other work of the muscular system.

Living organisms, such as man and horses, are constructed from tiers of systems within a system within a system. “The existence of discrete network within discrete networks in bones, cartilages, tendons and ligaments optimizes their structural efficiency as well as energy absorption.” (Christopher S. Chen and Donald E. Ingber. Tensegrity and mechanoregulation: from skeleton to cytoskeleton, 1999) The construction is clever but underlines the fact that while superficial systems can be directly influenced by the rider, deeper systems are out of reach. However, they are intricate part of efficiency, soundness and performances. This is where imagination enters the game. And even further, this is where the rider’s imagination needs to be supported by advanced understanding of equine biomechanics.

The horse mental processing became interested in furthering sophisticated coordination of the horse physique if the promise is ease, effortlessness and comfort. The rider knowledge can guide the horse mental processing toward the coordination of the horse physique optimally orchestrated for the effort. Once the horse’ cerebellum, olivary nuclei, basal nuclei, register ease and effortlessness, they became interested in recreating the proper body coordination and even furthering it. However, and for a long period of time, the horse will return during the training session and day after day, to familiar locomotor pattern. Horses can be rewired but only through the repetition of proper movement.

“Movements are generated by dedicated networks of nerve cells that contain the information that is necessary to activate motor neurons in the appropriated sequence and intensity to generate motor patterns. Such networks are referred to as CENTRAL PATTERNS GENERATORs, (CPGs). The most basic CPGs coordinate protective reflexes, swallowing or coughing. AT the next level are those that generate rhythmic movements. Some, such as respiratory CPGs, are active through life, but are modulated with changing metabolic demands. Others such as locomotor CPGs, are inactive at rest but can be turned on by signals from command centers.” (Sten Grillner, The Motor Infrastructure From Ion Channels To Neuronal Network.)

The central pattern generators involved in locomotion are off when the horse is standing still. Their education and reeducation can only be done through correct motion. This is where the rider’s imagination as to be supported by sound understanding of equine biomechanics. Once the rider has in mind the body coordination appropriated for the effort, the training session is a dialogue guiding the horse brain toward the correct orchestration of the many systems involved. The dialogue is balanced between the horse protecting muscle imbalance, morphological flaw or poor but familiar patterns, and the cerebellum and other elements of the brain monitoring the body, recognizing the ease and effortlessness associated with a precise coordination of the body.

The dialogue includes errors, frustration but also pleasure of being comfortable. It is necessary for the rider to understand that the horse is interested in finding effortlessness but he is also influenced by his central pattern generators that are used to function a different way. This is why the old adage emphasizing obedience, submission and other authoritarian approaches don’t give any chance for the horse to explore unknown combinations of reflexes and therefore error. Jean Luc Cornille

twitter

twitter facebook

facebook pinterest

pinterest yahoo

yahoo linkedin

linkedin