A New Approach To Lameness

A New Approach to Lameness

Image by ShortHorse Studios

Equine Ergonomics

“Movements are generated by dedicated networks of nerve cells that contain the information that is necessary to activate different motor neurons in the appropriate sequence and intensity to generate motor patterns”. (1) These networks are referred to as Central Pattern Generators (CPGs). Locomotors CPGs are inactive at rest. They are turned on when the horse is set in motion by signals from command centers. Unless the rider’s equitation specifically coordinates the horse’s physique to further the benefits of static therapies once the horse is set in motion, very little of these therapies will help the horse through gaits and performances.

“Since the growth of knowledge is the core of progress, the history of science ought to be the core of general history. Yet the main problems of life cannot be solved by men of science alone, or by artists and humanists: we need the cooperation of them all.” ( George Sarton) As well, neither the veterinarian, the farrier, or the therapist alone can solve the horse’s problem. A cooperation of them all, including the rider and the trainer is necessary. If after successful treatment and/or shoeing, the equitation that failed to efficiently prepare the horse’s physique for the athletic demand of the performance is applied again, the same or parallel injury is likely to reoccur.

The greatest discovery made by the practical application of advanced research studies is that the old adage, back soreness is only a compensation for hock pain or other musculoskeletal disorders, is inaccurate. In most instances back muscle imbalance or other vertebral column dysfunctions are the root cause of limbs kinematics abnormalities and consequent injuries. The second greatest discovery made by the practical application of advanced research studies is that the consensus ruling most equestrian theories as well as training techniques, the horse’s lower line, (abdominal and limbs muscles), is flexing the horse’s upper line, (the back), is inaccurate too.

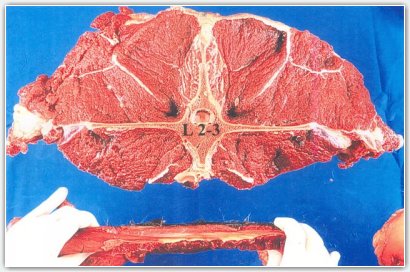

In the necropsy room, we sectioned vertically a specimen at the level of the second lumbar vertebra. The picture shows the very large

discrepancy between the mass and power of the back muscles, (upper half of the picture), by comparison to the size of the abdominal muscles, (lower half of the picture). Considering that in motion, abdominal muscles have to stabilize the gastro-intestinal track which is moving back and for like a piston, the thought that the abdominal muscles have the power to flex the mass of the back muscles is a leap of faith. Factual analysis suggests to the contrary that another and more powerful muscular system, the back muscles, is flexing the thoracolumbar spine.

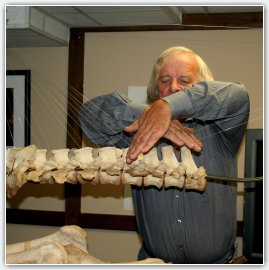

In 1976, James Rooney described the equine main back muscles as set in a mirror image direction. We explored how the rider’s equitation could

be modified in order to efficiently act on muscles working simultaneously while set in opposite directions. The research forced us to move away from the traditional driving seat which is stimulating earlier and stronger contraction of the muscle groups known as longissimus dorsi, over the muscle group set in the opposite direction and referred to as the multifidius system. Instead, we explored the thought that a more vertical posture, where the rider would be in exact balance over the seat bones, would create a neutral balance. Neutral balance means that the rider’s body weight is not acting back to front or front to back but rather exactly vertically on the horse’s back.

Regarding any shift of the rider’s weight as a nuisance is a pertinent thought but a not new idea. In the 17th century, the Duke of Newcastle taught that the rider’s pelvis should be held as still as possible. “A rider’s body should be divided in three parts, two of which are mobile and one which is not. The first of the two movable parts is the body down to the waist; the other is the leg from the knee downward. Therefore, the immovable part of the body is from the waist to the knees.” (Duke of Newcastle, 1592-1676) The thought that the pelvis should remain as immovable as possible implies reduced undulations of the lumbar vertebrae moving the practical application of advanced scientific discoveries further away from conventional equitation. However, once again, the concept is not new. Precursors have intuitively understood that a sound equitation demands a reduced motion of the rider’s vertebral column. “The subtle S-curve of the spine allows the spine to oscillate minutely, a movement so tiny that it is hardly perceptible to the naked eye, producing a “soft” seat. This “soft seat” differs fundamentally from a “doughy” seat, in which we find a spine that is too flexible and allowed to undulate freely in response to the horse’s movement.” (Waldemar Seunig).

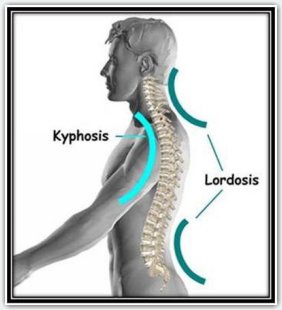

Very little movements occur in the rider’ cervical vertebrae but the alignment of the cervical vertebrae and head at the vertical of the vertebral column allows greater control of the whole vertebral column. The natural curve of the rider’s thoracic vertebrae is slightly concave and is usually referred to as kyphosis.

This part of the rider’s vertebral column is very important. In order to absorb the large range of motion induced on the rider‘s vertebral column from the horse’s limbs and body movements, the whole vertebral column needs to be involved. The problem is that the horse’s vertebral column is only capable of a very limited range of motion. If the rider absorbs the large range of forces coming from the horse’s legs and body movements through large undulation of the lumbar vertebrae, (a doughy seat), the rider might find some comfort for himself but is creating discomfort and protective reflex contraction of the horse’s back muscles.

The doughy seat comes from a misconception. Until technology permitted us to measure the possible range of motion of the horse’s thoracolumbar spine, our ancestors believed that the large sum of movements that they perceived in the saddle were due to large undulations of the horse’s vertebral column. This misinterpretation gave birth to the concept of the swinging back. Already in 1953, Milton Hildebrand pointed out that during locomotion, the movements of the horse’s vertebral column were extremely limited. “The thoracolumbar spine of the horse is kept virtually rigid during locomotion; the small movements that may be seen take place in the lumbosacral joint.” (2) Hildebrand’s observations did not faze the theologians of the equestrian world who preferred to believe that the horse’s thoracolumbar spine was swinging.

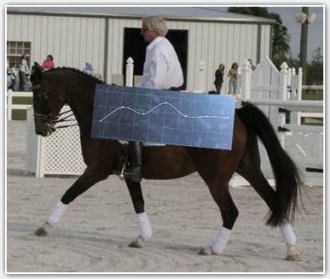

Since the range of motion of the horse’s thoracolumbar column is in fact relatively limited, the rider’s vertebral column needs simultaneously to absorb and reduce the sum of movements induced from the horse’s limbs into the rider’s vertebral column. On this picture, we placed seven sensors on the horse’s back. The sensors measure all type of accelerations. The computer program was set to measure exclusively the vertical forces created by the hind and front limbs. The greatest amount of vertical forces was registered by the sensor situated under the rider.

The rider’s spine needs to act as a shock absorbing mechanism dampening via movements, the forces induced from the horse’s limbs and body movements. But concurrently, the movements of the rider’s vertebral column needs to resist the forces induced from the horse, reducing the motion of the rider’s spine within the limits of the horse’s vertebral column’s possible range of motion. This double duty can be achieved using moderated motion of the whole vertebral column instead of large undulations of the lumbar vertebrae.

Riding this way, the rider and the horse’s vertebral column are functioning alike. The main function of the horse’s back muscles is not to increase the movements of the horse’s vertebral column but instead to reduce and maintain the motions of the horse’s thoracolumbar spine within the limits of its possible range of motion. Harmony between two partners can only be achieved dancing the same dance and when the horse and the rider are dancing the same dance the subtlety and efficiency of the conversation constantly evolve.

In fact, in terms of performance as well as the horse’s soundness, one can objectively talk about a new world. When James Rooney identified the kinematics abnormalities leading to hock problems, stifle issues, navicular syndrome, kissing spine, tearing of the deep flexor check ligament, sacroiliac strain and other injuries, no one investigated how to correct the kinematic abnormalities because the principles of equitation did not permit correction of these abnormalities. Even today where greater concern is given to the horse’s vertebral column, very few efficient solutions are offered because traditional equitation does not permit us to influence precisely and efficiently the biokinematics of the equine vertebral column.

Instead, riding principles updated to actual knowledge of the equine physiology allow a much more sophisticated education of the horse’s vertebral column and consequently, the capacity to correct limbs kinematics abnormalities beyond the limits of all existing therapies. Great riders who had the horsemanship to apply their skill for their horses’ soundness and performance instead of performance alone, have intuitively figured out the principles explained in this discussion. But their flair did not pass onto the next generation because the explanations remained within the limits of conventional thinking.

“The art of rehabilitation after injury is just becoming a serious field of study...” (Kristine Matlack DVM) The practical application of the knowledge developed through equine research needs great horsemen and women. Rehabilitation is an art. It is the higher rank of the equestrian art; performing in partnership with a horse optimally prepared for the athletic demand of performance and when the risk of intense competition does injure the horse, the same partnership is helping the horse to recover soundness.

However, the reality which needs to be clearly formulated is that rehabilitation cannot be achieved applying the principles of riding and training that caused the injury. As Albert Einstein said , “The significant problems we face today cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them.”

Jean Luc Cornille

Jean Luc Cornille Equine Ergonomist Copyright©2011

Our In-Hand equine Biomechanics Course

References

(1)-(The motor infrastructure: From Ion Channel to Neuronal Networks. Sten Grillner. Nature review/neuroscience, volume 4/ July 2003. 573-585).

(2)-(Milton Hildebrand, 1959, Motions of the running cheetah and horse. mammals. 40, 481-495)

Kissing Spine article by Jean Luc