Mechanoresponsiveness 16

Mechanoresponsiveness 16

Inward rotations of the hock

Jean Luc Cornille

Take a bamboo pole. Cut a small segment, drill one hole at one end and several holes at the other end, you can blow air at one extremity, modulate the air flow with the fingers covering the holes and play music. You have found the only harmless way to use a bamboo pole. The other music, the one played touching the horse limbs is a cacophony altering proper synchronization between flexion, extension and inward rotation of the joints.

Synchronized with each flexion and extension of the hip, stifle, hock, fetlock, an inward rotation occurs, medial to lateral and lateral to medial, around the vertical axis of the bone. Most of the joints have an irregular shape designed for a combination of flexion, extension and inward rotation. With each stride, sound locomotion requires precise synchronization between flexion and extension of the joints and their inward rotations. When proper synchronization between the moving parts is altered, shearing forces occur and arthritis develops.

“It is hoped that consideration of the normal system will illumine abnormal as well as the abnormal illumining the normal. “ (James Rooney, Biomechanics of lameness in horses) We start with the normal synchronization between flexion, extension and inward rotation. Then, it will be easy to understand why and how training techniques acting on the lower leg without adequate kinematics of the upper leg and in relation to the thoracolumbar spine mechanism, induces shearing forces on the joints and consequent injuries.

The normal.

During the stance, which is the time the hoof in on the ground, a subtle coordination of flexion, extension and rotation induce static and sliding frictions on the surfaces of the joints. Static frictions are greater than sliding frictions but they all reach maximum intensity at the end of the propulsive phase where maximum forces are exerted on the joints. “The development of shearing forces between the joint surfaces may be expected when the forces exerted on the joints are maximal. In the rear leg, forces exerted by and on the leg is maximal at the end of the stride, just before the hoof leaves the ground.” (James R. Rooney)

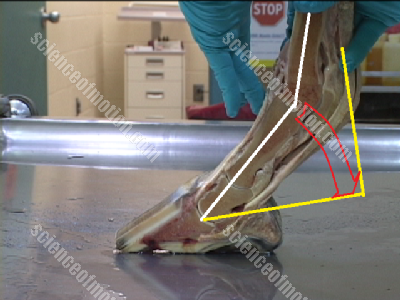

Frame by frame, we can easily visualize and understand how parts articulate around each other. Before the hoof contacts the ground, the tibia has, by extension of the stifle, rotated around its long axis from medial to lateral. (medial to lateral means from the inside, medial, to the outside, lateral).

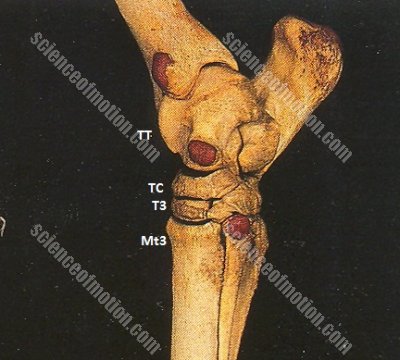

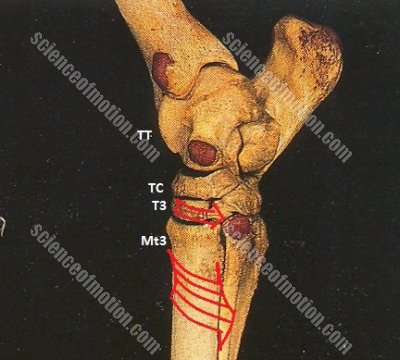

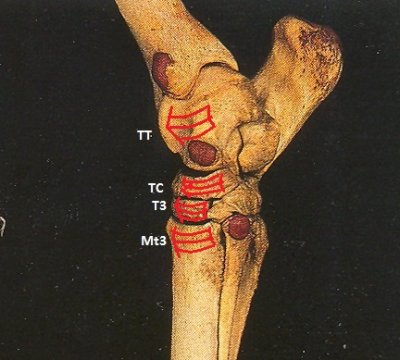

At the moment of impact, Mt3 and T3 may be considered to be stationary. The tibiotarsal bone, (TT) and central tarsal bone, (TC) are also stationary.

A slight flexion of the hock and stifle may occur at impact inducing a minute rotation lateral to medial of the tibiotarsal joint, (TT) and central tarsal joint, (TC)

Lower in the leg, dorsiflexion of the fetlock causes a lateral rotation around its long axis of Mt3.

This rotation of the canon bone, (Mt3), induces a medial to lateral rotation of Mt3 and T3.

In the hock joint, which is composed of Mt3, T3, TC and TT, we have at this instant a medial to lateral rotation of Mt3 and T3 while the two higher components of the joints TT and TC are held stationary or rotate slightly in the opposite direction.

This is a stable coordination, which provides for maximum contact of joint surfaces and thereby gives maximum stability and maximum surface for weight bearing. These conditions pertain until the second half of the stride.

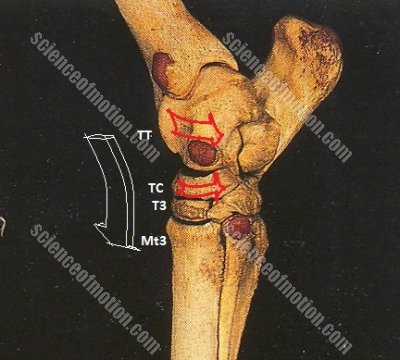

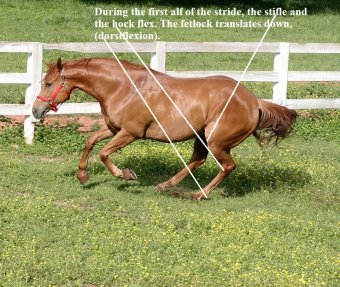

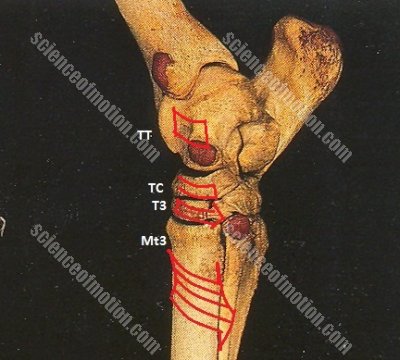

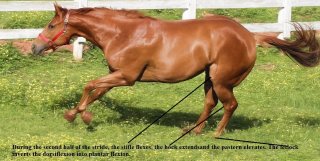

During the second half of the stride,  the stifle and the hock extends and the pastern elevates. It is the moment where the hind leg exerts its maximum propulsive activity.

the stifle and the hock extends and the pastern elevates. It is the moment where the hind leg exerts its maximum propulsive activity.  The tibia rotate medially as well as TT and TC. Simultaneously, the pastern elevates converting the dorsi-flexion of the fetlock into plantar flexion. The inversion from dorsi-flexion of the fetlock into plantar flexion, induces a medial rotation of Mt3 and T3. The hoof then clears the ground and the hind limb moves forward into the swing phase.

The tibia rotate medially as well as TT and TC. Simultaneously, the pastern elevates converting the dorsi-flexion of the fetlock into plantar flexion. The inversion from dorsi-flexion of the fetlock into plantar flexion, induces a medial rotation of Mt3 and T3. The hoof then clears the ground and the hind limb moves forward into the swing phase.

This is, frame by frame, the normal synchronization between flexion, extension and inward rotation of the different parts of the hock joint during locomotion. We always warn against activating the hind legs with a bamboo pole or a whip. You can now understand how these practices alter proper synchronization between flexion and extension of the joints and their inward rotation. Classic authors used the technique because they were not aware of the internal rotations of the joints. It is doubtful that they would keep promoting the practice in the light of new knowledge.

Proponents of these archaic approaches will argue about details such as where the pole touch the horse. This is the classical form of deny that always resists pertinent discoveries. In 1856, Schopenhauer wrote, “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” (Arthur Schopenhauer, 1788-1860) Truly, it does not matter where the pole touches the leg. As long as the kinematics of the lower leg is modified without adequate kinematics of the higher leg and in relation to the vertebral column mechanism, synchronization between flexion, extension and inward rotation of the joints is altered and arthritis develops. There is no substitute to sound education.

The biomechanics of the vertebral column form the basis of all body movements, including limbs movements. The equestrian art is truly an art and cannot be achieve without understanding and respecting how the horse’s physique effectively works. “The ability of the artist to express the beauty of the human form is predicated on a profound study of the science of anatomy.” (Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519) Leonardo also described the achievements of the ones who act on the leg without understanding that sound limbs movements are the outcome of proper vertebral column mechanism. “Lacking an appreciation born of a detailed analysis of bone structure and muscular relationship, the would-be artist was liable to draw wooden and graceless forms that seem rather as if you were looking at a stack of nuts than a human form, or a bundle of radishes rather than muscles.” (Leonardo da Vinci)

Acting on the legs is not the only possible disturbance. Morphological flaws can create kinematics abnormalities, as well as load on the forelegs and training misconceptions rushing the horse faster than its natural cadence. Rooney described how straight hock conformation is prone to arthritis between Mt3 and T3. Training misconceptions creates functional straight hock, which induce the same aberrant stresses on the hocks than the morphological defect. Functional straight hocks are training misconceptions that create early impact of the lower hind leg. On the other side of kinematics abnormalities, functional sickle hocks will create the same stresses on the joint than the morphological defect.

The theme of our 2016 Science of Motion International Conference that will be held, as traditionally, during the first week end of October, (October first and second), is the biomechanics of soundness. We will explain and demonstrate with bone manipulations, computer analysis and videos, the proper biomechanics of the hind and front legs. We will also demonstrate with horses working in the training ring, the kinematics abnormalities causing abnormal synchronization between flexion, extension and inward rotations of the joints. In line with the principles of the science of motion, being aware of the problem is the first step toward correcting the problem. Limbs kinematics abnormalities are the outcome of improper functioning of the thoracolumbar spine. Working the horses in the ring, we will demonstrate how correcting the work of the thoracolumbar spine, remedies the kinematic abnormality altering proper functioning of the hock.

Jean Luc Cornille

Learn about our online and mail order course IHTC

twitter

twitter facebook

facebook google

google pinterest

pinterest myspace

myspace linkedin

linkedin