Halfpass

Half-Pass

From Tradition to Science

Jean Luc Cornille

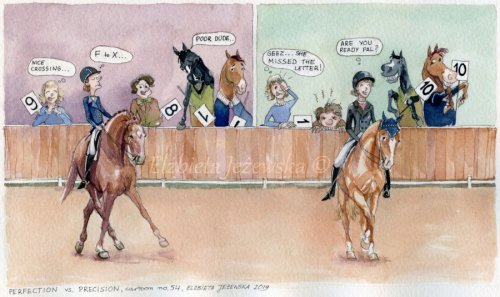

Beautiful painting by Elzbieta Jezewska

Members of the Science of Motion immediately picked up the inverted rotation associated with the left lateral bending of the left horse as well as the excessive and late fetlock dorsiflexion of the right front leg due to the increased load created by the inverted rotation. On the left picture, the judges did not notice the inverted rotation but the horses did. On the right picture, the horses celebrated the proper correlation between lateral bending and transversal rotation, but the judges remain at the level of superficial details.

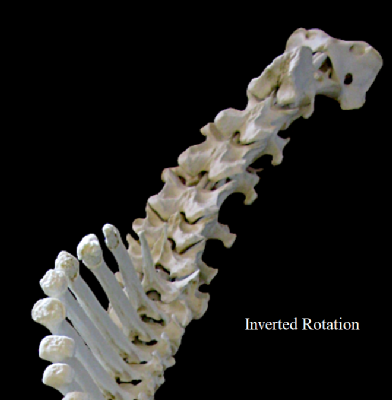

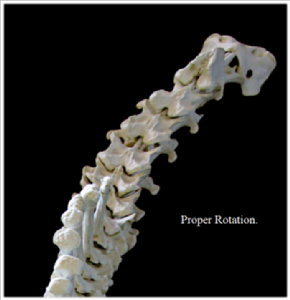

Inverted rotation.  Proper rotation.

Proper rotation.

Both photos are viewed from the saddle. The right lateral bending coupled with an inverted rotation is exhibited by the horse on the left. By contrast, right lateral bending coupled with the correct transversal rotation is exhibited by the horse on the right.

In 1949, General Decarpentry completed “Academic Equitation.” The master piece became a classic of equestrian literature. His study of Half -Pass is based on the knowledge that was available at this time, consequently and not surprisingly, there are statements and beliefs that are no longer in line with actual knowledge.

For instance, the discussion about the bending of the horse’s vertebral column during the half pass is clouded.  To the defense of both, General L’Hotte and General Decarpentry, the consensus was at this time, that the horse’s vertebral column bends all the way evenly. Almost two decades later, Richard Tucker illustrates the belief of the thoracolumbar spine continual curve, drawing the lateral bending of the equine thoracolumbar spine. Tucker simplified the vertebral bodies as rectangles. His belief was that during lateral bending the corner of the rectangles and therefore one side of the vertebral bodies, come in contact. This belief has been contradicted buy actual knowledge. Tucker completed in 1964 the first dynamics analysis of the equine thoracolumbar spine. (Richard Tucker, Contribution to the Biomechanics of the vertebral Column, Acta Thoeriologica, VOL. IX, 13: 171-192, BIALOWIEZA, 30. XL. 1964)

To the defense of both, General L’Hotte and General Decarpentry, the consensus was at this time, that the horse’s vertebral column bends all the way evenly. Almost two decades later, Richard Tucker illustrates the belief of the thoracolumbar spine continual curve, drawing the lateral bending of the equine thoracolumbar spine. Tucker simplified the vertebral bodies as rectangles. His belief was that during lateral bending the corner of the rectangles and therefore one side of the vertebral bodies, come in contact. This belief has been contradicted buy actual knowledge. Tucker completed in 1964 the first dynamics analysis of the equine thoracolumbar spine. (Richard Tucker, Contribution to the Biomechanics of the vertebral Column, Acta Thoeriologica, VOL. IX, 13: 171-192, BIALOWIEZA, 30. XL. 1964)

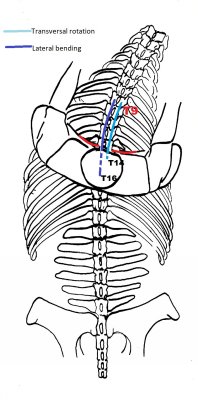

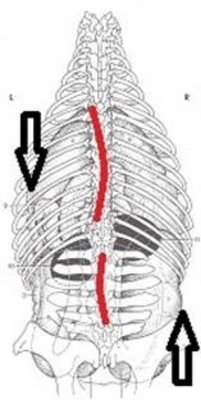

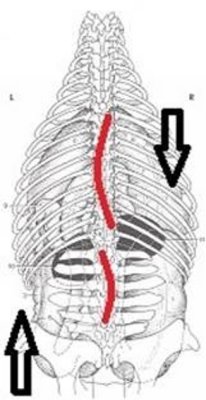

Measurements, later demonstrated that lateral bending of the thoracic spine occurred mostly between T16 and T9. The associated rotation is localized between T14 and T9.

The lumbar vertebrae have their own capacity of lateral bending mostly between L1 and L5.

In motion, the thoracic spine bends left with the backward movement of the left front leg and the lumbar spine bends right with the forward swing of the right hind leg, and vice versa.

In Decarpentry’s study, the relation between thoracolumbar column function and limbs kinematics is resumed to visual observation and logical deduction. At the eighteen centuries, The Marquis of Condorcet (1743-1794) believed that the study of anatomy was already completed. Through necropsy, they observed the attachment and insertion of muscles and theorized their action on the joints. In the light of actual knowledge, the belief appears naive. However, Condorcet was a very intelligent man. He was in 1791 President of the French legislative assemble, and proposed a grandiose plan of public education. Knowledge evolves and classical authors explain their experience and thoughts based on the knowledge available to them. Decarpentry was not aware of the faculty of storage and reuse of elastic energy. He was on the belief that elongating a muscle elongates the amplitude of the stride. It took Centuries for equine research to understand that the horse’s biological mechanism functions under totally different rules. “Most of the length change required for the work of locomotion, occurs not in the muscle fibers themselves but by elastic recoil of the associated tendons and muscles aponeurosis.” (The role of the extrinsic thoracic limb muscles in equine locomotion. R. C. Payne, P. Veenman and A. M. Wilson. J. Anat. (2005) 206, pp 193-404).

Paraphrasing Will Roger, “The trouble with political jokes is that very often they get elected.” They get elected because peoples are educated just enough to believe what they have been taught and not educated enough to question what they have been taught. Questioning what we have been taught is our responsibility as a rider. The wisdom of our ancestors is not printed in the lines of their book, the wisdom is hinted between the lines needing to be updated to actual knowledge.

.

General L’Hotte (1825-1904) for instance, observed that during half-pass the outside foreleg has to pass in front of and around the inside foreleg, and concluded that half-pass develops the amplitude of the forelegs’ movements.  A great part of the foreleg’s swing is the outcome of elastic energy stored in tendons, muscles, aponeurosis and fascia during the stance. The evolution of knowledge lead Jean Marie Denoix to explain in 1984 that half-pass develops, indeed, the propulsive power of the forelegs.

A great part of the foreleg’s swing is the outcome of elastic energy stored in tendons, muscles, aponeurosis and fascia during the stance. The evolution of knowledge lead Jean Marie Denoix to explain in 1984 that half-pass develops, indeed, the propulsive power of the forelegs.

When it come to the distribution of the weight, many statements are contradicted by actual knowledge. In 1949, the phenomenon of transversal rotation and never the less, the problem of inverted rotation was not known. In Decarpentry’s work, the deductions of weight associated with lateral bending of the thoracolumbar spine do not take into consideration the effects of proper as well as inverted rotations.

The overall idea is that the movement educates the horse’s physique. There is no concern for the fact that the horse will execute the move protecting his actual body state, muscle imbalance, morphological flaw and even memory of pain. If the horse expresses difficulties, patience is advised but basically also, repeating the same aids and expecting a different result.

Dressage movements were originally gymnastic exercises designed to prepare the horse athletically for the demands of war, farming, or urban activities. When dressage movements became compulsories ordered in dressage tests, standards of judgment defined how the movements were supposed to be presented. Judging standards focused on esthetics without much understanding of the underlying biomechanics factors.

The greatness of new knowledge and in particular, the practical application of new knowledge, is the capacity to coordinate efficiently the horse’s physique for the athletic demand of the move. Decarpentry hinted at the idea that dressage movements can be therapeutic but if the education is about the submission to the rider’s aids, the movements are more likely going to hurt the horse. Without adequate knowledge and an equitation guiding the horse’s brain toward the coordination of the horse’s physique, dressage movements have become compulsories executed by talented yet dysfunctional horses harming instead of educating the horse.

In this series, we expose first, integrally and to the letter, the thoughts of our ancestors. We study then the athletic demands of the move and the body coordination allowing the horse to benefit from the gymnastic exercise. Jean Luc

Half-Pass

(Below From Decarpentry)

“In the half-pass, the horse displaces his shoulders and his haunches simultaneously toward the same side.

If the lateral extension of the limbs is equal in front and behind, the horse moves in a direction parallel to himself. His limbs follow straight parallel tracks, at an angle with the direction in which he faces. This is a half-pass on a straight line.

If the lateral extension of the shoulders is greater that of the hunches, the limbs describe concentric circles. It is the half-pass on a circle, the haunches-in, and its limit is the pirouette

In the opposite case, it is the half-pass on a circle, the haunches-out, the limit of which is the reversed pirouette.

In the half-Pass on the straight line, the horse can be straight in his long axis from the head to tail.

However, says General L’Hotte, in side steps, there is a good reason for demanding a slight flexion of the poll, (le placer trouve sa place). It compels the horse to look in the direction of the movement and it helps in bringing forward the outside shoulder which has the harder task.

“For all that, it (the flexion) must be very slight so that the action of the rein producing the flexion does not react on the haunches.” It is difficult to imagine that a bend imposed on one extremity of the spine will not be communicated to the other end. However, the flexion can be so light that it is unnoticeable, or it can even be reduced to a mere tendency.

This tendency of itself can even be favorable to the desired movement, for when a horse in inflexed in the (Mise en Main) his haunches always tend to displace themselves in the same direction as his head, which is the object of the half-pass. What we must avoid is an excessive bend on the side of the half-pass which would react on the shoulders by pushing them toward the other side.

The degree of flexion must be proportionate to the degree of the half-pass. The old masters used to say; “For a half-hip, the rider must see the corner of the horse’s eye, for a whole hip (45° and more) the rider must be able to see the ball of the eye scintillating.”

What matter mostly is that the rider should be able to regulate the action of the rein producing the flexion so that it achieves the required effect and not the opposite one. For example, if to produce a right flexion, the rider draws the right rein toward the hip by pressing it somewhat against the neck, he transfers the weight of the neck onto the left shoulder, thereby hindering it instead of assisting it.

Therefore, when demanding flexion, the hand must act in its normal position, or even outwards but never inwards unless the rider needs to moderate the displacement of the left shoulder toward the right which happens rarely.

Influence of flexion on the movement of the limbs in the half-pass.

We should note that the lateral flexion of the horse influences the movements of the limbs in two-track work.

The leg on the concave side come closer to one another, and those on the convex side extend further apart from one another.

Consequently, the inside fore is relatively behind the outside fore, and the inside hind is relatively in front of the outside hind.

The effort of stepping across is therefore less for the limb which is forward, and greater for the one which is behind. Thus, in the shoulder-in, in which the horse moves in a direction opposed to his inflexion, the hind legs exert less effort in crossing themselves, and the forelegs have to make a greater effort.

It is the contrary that happens in the half-pass.

Influence of the straightness or curvature of a course on the movements of the limbs in the half-pass.

We should note also that in two-track work on the circle, the movements of the limbs are influenced by their position in relation to the direction of the movement.

When the hind-quarters are inside the circle, as in the haunches-in, the displacement of the hind limbs is smaller than that of the fore-limbs; the later have to reach out more.

In the half-pass on the circle with the haunches-out, the opposite obtains.

Execution of the Half-Pass

The horse that is already proficient at the shoulder-in and at the haunches-in will usually experience no difficulty in executing the first half-passes demanded of him, though of course on a very slight oblique.

However, in most cases, he will tend to slow his pace considerably. The trainer will therefore, have to pay to the maintenance, or rather to the restoration of impulsion. To start with, he will resort to the convention established between himself and the horse from the beginning of dressage. When the rider rises at the trot, the horse must go into a more extended trot, and he will ensure the observance of this convention by the use, if necessary, of the legs and the whip.

But whether to rise on one or on the other leg is not an indifferent matter. In theory, it would appear logical to rise on the diagonal which is on the side of the direction of the half-pass; as the hind leg of this diagonal tends to be drawn forward this side. This procedure should facilitate the effort of crossing.

It happens sometimes, however, that a horse restricts the movement of the outside diagonal because, as we explained at the beginning of the present chapter, he does not engage the inside hind leg; in such case, we should trot on the outside diagonal.

Here again, despite the most attentive observation and the cleverest arguments, experience is the only thing that counts. It is by trial and error that the trainer must discover which diagonal gives the best results, and it is on this one that we must rise.

Finally, he can also resort to trotting uphill to re-establish impulsion, a task which must be pursued until complete success is achieved.

The same applies to the use of the aids.

Theoretically, a slight flexion in the direction of the half-pass would draw the outside shoulder in this direction and “facilitate” the movement. Practically, this is not invariably so at the outset. The horse frequently finds it easier to obey if he is not flexed, or even if he is flexed very slightly in the opposite direction.

There is no reason why we should deprive ourselves of a mean of achieving the most immediate aim, which is to make our intension clear. Once the horse has overcome his initial clumsiness, he will obey the aids instead of distorting their effects by resistances the origin of which eludes us, and we will then have no difficulty in returning gradually to the normal use of the aids which assures utmost regularity of the movements when the horse is completely unconstrained.

The same method of trial and error must be applied to the use of the heels, and we should not be too hidebound to modify their point of application if experience shows that this yields certain advantages at the beginning in producing the movement; as suppleness improves, we will gradually be able to return to a normal use.

Once it is effective, in half-pass to the right for example, the right rein leads the horse and give him a suitable flexion with a direct or slight opening action; the left rein must be ready to limit the bend if necessary, and also acts as an indirect rein pushing the shoulders toward the right. The left heel acts in the direction of the half-pass to push the whole mass in that direction. With an action from back to front, the right heel firmly sustains the impulsion and preserve the inside hind (right hind) from escaping. However, perfection and consequently perfect lightness in the half-pass can only be entirely achieved once the indirect rein on its own suffices to produce the movement. It is with this ultimate aim in view that the rider must strive to improve the use of the aids.

We gradually increase the periods of exercise in the half-pass, always only very slightly oblique, until the horse can execute it with the utmost facility, resume at straight line (or a circular one if he is inflexed), and half-pass once again, without altering the pace and the rhythm and even lengthening the stride if the rider demands.

It is unnecessary and even detrimental to attempt to obtain too soon a half pass extending 25 to 30 degrees in inclination.

The practice of the half-pass on the circle, with a slight degree of inclination enables the trainer to develop separately the capacity for lateral movement of the haunches and the shoulders.

In the haunches-out on the circle, the haunches have to make a greater lateral effort than the shoulders as they have to cover a greater distance; as the hind quarters are usually the least mobile part of the horse in sideways movement, this exercise is the most useful one at the beginning, and is succeeded by the exercise of the haunches-in at a later stage. In the opposite case (when the forehand is least mobile) the haunches-in on the circle would come first.

When the horse can execute both these exercises on a circle easily, at an angle of 23 degrees for example, he is ready to half-pass at an angle of 30 degree on a straight line, and so on.

The half-pass must be frequently alternated with the shoulder-in which is not just a preparatory exercise for the half pass, but of itself is an excellent way of suppling and developing the muscles.

Assuming an equal degree of inclination in either exercise, the play of the limbs will be very different as the inflexion of the horse modifies the distribution of his weight, loads the limbs on the concave side and thus unburdens the others.

For example, if the movement is executed from left to right, the thrust of the left hind determines the direction of march in both cases, but this leg will be loaded in the shoulder-in and unloaded in the half-pass. The right shoulder will support more weight in the half-pass when it is on the concave side, its lightened in the shoulder-in. Its forward extension towards the right will necessarily be affected differently by each exercise.

Thus, the trainer can adapt the exercise to the peculiarities of the play of the locomotive system of his pupil.

If for example, the horse’s right diagonal is akward, the left hind failing to engage and the right for to extend properly, the trainer corrects this:

- by resorting to the left shoulder-in, on straight lines and also especially on circles to the right (sometimes called counter shoulder in);

- by practicing the half -pass to the right, on straight lines and also and expecially on circles to the right hand with the haunches-in.

During all these exercises, the use of the rising trot will contribute its own particular effects, and the practice of riding uphill on straight lines should also be restored too.

At the beginning, side-stepping, if it has been done without inflexion, must finish with a few straight strides in a straight line, but if done with inflexion, then must be completed by single track movement on a large circle corresponding to the inflexion. In the latter case, the alternations must be separated and connected by a few straight strides before the opposite bend is demanded.

Later on, when the horse has become proficient at counter-changes on two-tracks, the transition from one form of side-stepping to the other can be executed directly. For example, without altering the direction of movement, we can change from the left shoulder-in to the right half-pass , first without flexion, then with flexion. By altering the direction of movement, we can change from the left shoulder-in to the left half-pass and conversely.

All these exercises considerably improve the horse’s agility and his submissiveness to an extent where we get the feeling of being able almost to “knead” him with the aids.

It should be noted finally that, in the half-pass, the indirect rein on the side opposite to the direction of movement must be gradually substituted for the action of the leg on that side, until it even completely replaces it (Du Paty du Calm, and Faverot de Kerbrecht).

Perfecting two-track work by the use of the walk.

In side-stepping, the efforts of the limbs to cross in front of one another can only be entirely exploited at the walk, because at the trot the moment of suspension enables the horse to avoids a true crossing by “disengaging” prematurely the leg to be crossed.

At the walk, on the other hand, the crossing is complete, and consequently the suppling effect on the adductor and abductor muscles of all four limbs and (especially) of the back produced by the crossing of the hind legs is much greater and more effective than at the trot.

It is useful therefore to start all over again, and to perfect at the walk, where greater effort is required, the work on two-tracks which was started at the trot because the moments of suspension made the task easier for the horse.

Furthermore at the trot, in the exercises of the haunches-in and the haunches-out on the circle we cannot complete the gradual reduction of the radius which leads to the pirouette or to the reverse pirouette, as it is not possible for the horse to continue to trot on the spot with the forelegs or with the hind legs before he can execute a piaffer.

It is therefore at the walk also, and especially at the School walk, that we must seek to perfect the movements of haunches-in and haunches-out, and that we will be able to exploit to the full the very important advantages of the pirouette.